28 Aug 1842 – 15 Feb 1898

Son of Philip Cardon and Martha Marie Tourn

Life Sketch of Thomas Barthelemy Cardon

Thomas Barthelemy Cardon is the son and ninth child of Martha Marie Tourn and Philip (Philippe) Cardon. Born in Prarostino, Turin, Italy on August 28th, 1842. He married Lucy Smith November 13, 1871, in Logan, Utah.

1) Married to Lucy SMITH on November 13th, 1871, 2) Married to Amalie Bolette Jensine JENSEN on July 24th, 1884, 3) Married to Ella Clarinda HINCKLEY on June 24th, 1885.

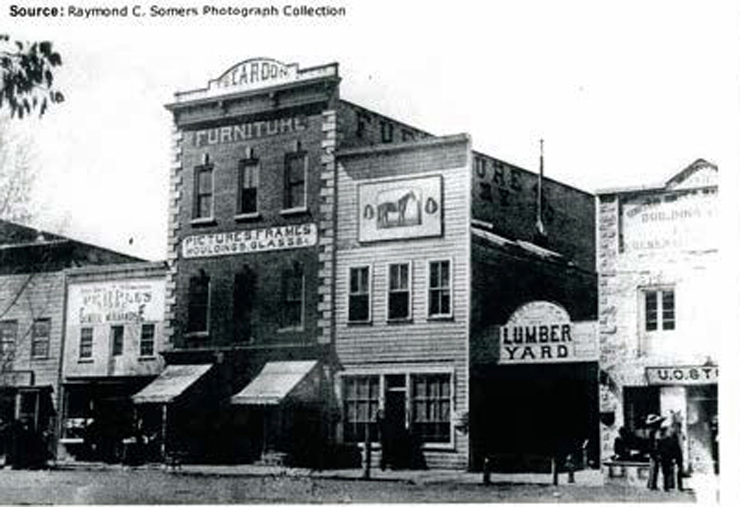

Thomas B. Cardon settled at Logan in 1867 and established the first watch making and jewelry store in the Valley where Ruchti, the tailor, was located, west of First North. In 1872 he added to it photography and a fine art gallery. Being of an enterprising nature he branched out in 1881, erected a large three-story cut stone and brick building, now occupied by the Logan Hardware Company. It was the first business house of this size in the city. Here also the Thatcher Bank opened its banking establishment, the first in the Valley.

Mr. Cardon by nature was an artist and possessed an artistic temperament. He was born in Italy, the land of art and genius, and this native instinct was brought into his profession as photographer and jeweler. For years his photographs adorned many of the homes in the Valley and many of his watches are still in evidence. That this native artistic disposition was transmitted to his children is very evident from the appearance of the business houses represented by them in the city at present.

Children: Thomas LeRoy Cardon, Edna Lucy Cardon Langton, Eugene Cardon, Elmer Cardon, Ariel Frederick Cardon, Margaret (Grehta) Cardon Rechow, Bartlie Temple Cardon, Orson Guy Cardon, Phillippe Vincent Cardon, Alice Lucile Cardon, Claire Cardon Sullivan

Posted by Eowyn Langholf to her family history blog

Heart Throbs Of The West

Thomas B. Cardon was the first watchmaker and repairman in Logan. He was a native of Piedmont, Italy, and came, with his father’s family, to Utah in 1854, locating in North Ogden. While living there he went to Camp Floyd to work. There he met a Frenchman, who was a watchmaker, who taught Thomas the watchmaking trade. He joined the army of the North and fought all during the Civil War. While he was away his father and family moved to Logan and upon his return from the army he came to Logan and in 1872 he opened a small watchmaking shop, the first in Logan, on First North between Main and First West Streets. He gradually added jewelry and photography to his business and continued this business as long as he lived and at his death his son continued.

Tullidge’s Histories Extract

Page 159

Thomas B. Cardon

Thomas Bartelemy Cardon, one of the principal business men of Cache County, who for many years

served the municipality of Logan, both as city recorder and alderman, is by birth an Italian. He is the son of Philippe Cardon and Martha Maria Tourn Cardon. He was born at Brae Prarustin, near Pignerolo, Piedmont, Italy, August 28th, 1842. His parents, like their ancestors for ages past were born and educated in the faith of the Vaudois, or Waldenese, whose religious tenets date back to apostolic days, independently of the church of Rome with which they claimed no affiliation, and to which they neither owed nor rendered any allegiance.

From the fourteenth century down to the final cessation of hostilities against them in the eighteenth century, their forefathers were persecuted for the firm adherence to their religious convictions. They willingly endured ostracism, exile, imprisonment, the numerous cruelties, the inhuman and unnameable barbarities which their foes, led on by fanatical priests, inflicted upon them, because they would not knowingly bow their knees to Baal and worship at a false shrine. They were unmoved. They remained true to their honest convictions and worshiped the Almighty God according to the best light and knowledge they possessed of Him.

The oppressions they had suffered, their earnest desire for and constant search after gospel

intelligence, and the general knowledge which they possessed of the scriptures prepared the minds of the parents of Thomas B. Cardon, to receive the greater light when it was brought to them by men delegated with authority to preach the gospel and administer its ordinances to all who would accept it. Hence it was with great joy that they welcomed Apostle Lorenzo Snow, Elders Jabez Woodward, George D. Keaton and others who first introduced the pure gospel of the Son of God to them in their own sunny climes of Italy. In 1852 his father and mother, his brothers John, Paul, Louis Philippe; and his sisters Catherine and Marie Magdeliene were baptized in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

The family continued to reside in their native land and to sustain, according to their ability, the

church whose doctrines they had espoused, until 1854, when being anxious to gather and associate with the body of their religionists, they emigrated to Utah.

Arriving in Liverpool (the great shipping place of the Saints from all parts of Europe) the family was organized with the company that sailed on board the ship John M. Woods, on the 12th day of March, 1854, and landed at New Orleans on the 1st of May, after a passage of fifty-one days. After resting a few days to recuperate from the prosecution of the long and arduous journey across the plains, they proceeded by steam-boat to St. Louis, and from there to Kansas City, Missouri. At Kansas City they procured their outfit for their overland journey across the western plains to Salt Lake City. While at Kansas City, young Cardon was attacked by the cholera, which was fatally prevalent at that place. The boy, as well as his parents, had strong faith in the efficacy of the

Page 160

ordinances of the Church to heal the sick, so he called upon the Elders to lay their hands upon him, and administer to him, and he was immediately healed.

In due time the outfit was completed, and the family started across the plains to make their home

with the saints in the valleys of the Rocky Mountains. They arrived in Salt Lake City in October, 1854.

From Salt Lake City the family moved to Mound Fort, near Ogden City, where they went into winter quarters, and in the following spring they moved to Marriotts where they remained until 1858.

In this year occurred what is known as the “move South” and in this general exodus of the people

from the northern settlements the Cardon family participated.

After the “Utah War” was over and peace proclaimed, Thomas B. Cardon, who had been detailed as one of the home guard, assisted the family in their return to their home in Weber County.

In the fall of 1858, young Cardon visited Camp Floyd for the purpose of obtaining employment. Hitherto his opportunities for acquiring an education had been very meager, and one of his objects in

seeking employment at Camp Floyd was that he might devote his surplus earnings for his tuition. At the Camp he met a number of his countrymen, who had enlisted in Johnston’s army, and the soldiers, told him that if he would enlist he would have the privilege of attending the school in the camp, free. Thus induced, he enlisted as bugler in Company G, United States 10th Infantry. However, he did not attend school, but received his education in the English language from a comrade who came from New Orleans and who, like himself, spoke French. This man’s name was Eugene Le Roy. So anxious was young Cardon to store his mind with a fund of useful knowledge that he frequently pursued his studies all night until daylight. Thus from a natural love of intellectual and moral culture, pursued industriously through life, Mr. Cardon became a fairly-educated man.

A curious and somewhat embarrassing error occurred in his enlistment. In making out the

enlistment papers, he was enrolled as Thomas Gordon. The mistake was not discovered until it was too late to be corrected, in consequence of which he served four years and a half in the army under that name.

While at Camp Floyd the company to which Mr. Cardon belonged was detailed to go south to meet

the United States pay-master, who was en route under escort from California to Utah. They marched as far as Santa Clara River, where they met the pay officer and escorted him to Camp Floyd. Judge Cradlebaugh was with the escort going south. He went out to investigate the matters connected with the horrible massacre, which was perpetrated at Mountain Meadows in 1857.

In the spring of 1860, the company to which Mr. Cardon belonged was sent to Fort Bridger to relieve other companies who had been ordered elsewhere.

In the fall of that year, being tired of an inactive life, Bugler Cardon applied for his discharge, and

would have received it but it was delayed and had not arrived when, in 1861, the Civil war broke out; so Thomas withdrew his application and went with his company on a forced march to Fort Leavenworth, en route to Washington D. C. They wintered at the national capital.

On March 10th, 1862, they were called into active service. They crossed Long Bridge en route to the Battle of Manasseh, when a ghastly sight was witnessed by young Cardon and his comrades. The bodies of many of the victims who had

PAGE 161

fallen at the battle which had been recently fought had been recovered from the river and stacked up on either side of the bridge. That terrible scene had a very powerful effect on the mind of the youthful soldier. There he received his first impressions of the horrors of the fratricidal strife that was then raging. The impressions produced upon his mind by the horrid spectacle he then witnessed he has never forgotten.

He was with the head-quarters of General George B. McClellan from the opening of the campaign in 1862 in Virginia, until after the battle of Malvern Hill. He was in active engagements at the battles of Big Bethel, the capture of Yorktown, at Williamsburg, Fair Oaks, etc. He also participated in the memorable seven days fight before Richmond, which began June 26th in which the Federal losses were severe and very heavy. At the battle of Gaines Hill the brigade to which Cardon belonged was placed in a very critical position, being between the two hostile forces and exposed to the firing of both armies.

On the 27th of June Thomas fell by the bullets of the enemy. He was wounded in the left arm, and in the left side. He was picked up and taken by comrades to the temporary hospital. They had proceeded with him but a few yards when a leg of one of his supporters was severed from his body by the explosion of a bombshell; and they had only moved a few paces further forward when another of his comrades fell dead at his side. He was killed by a ball from the rifle of one of the enemy’s sharp-shooters. It was from a similar source that Thomas Cardon received his wounds. At the hospital the army surgeons had decided to amputate Cardon’s arm, and he was left among the others to await the convenience of the doctors to deprive him of that limb. Meanwhile the patient swooned. So lifeless did he seem that he was reported dead, and consequently left in the charnel house with the corpses of those who had died of their wounds. That night the Union army retreated across the Chickahominy. About daylight on the morning of the 28th Thomas Cardon revived. On looking around him he beheld a scene which almost paralyzed him. The mangled bodies of many of his comrades lay there rigid in death, far from home, friends and loved ones, no mother, sister or wife to close their eyes or hear them breathe their sad but fond farewell to earth and all it held most dear to them.

With heartfelt gratitude to God that his own life had been almost miraculously preserved, and that

he was still in possession of all the members of his body, Thomas arose to his feet. He was very weak from the effects of his wounds and the loss of blood; nevertheless glad to escape from the scene of horror he started out to find and join his brigade. He had not gone far before he was seen by the enemy’s pickets and pursued by them; but fortunately he escaped being captured and reached the Union army in safety. In time Thomas recovered. His wounds were healed, but he was rendered incapable for further actual service, and on February 2nd, 1863, he was honorably discharged. He receives a pension of ten dollars per month for the hazardous services which he rendered to his country in defense of the Union. His discharge was delivered to him about 4 P.M. at the convalescent camp near Alexander. Thirty minutes later he was on the railroad train wending his way to the seat of the National Government. He tarried at Washington one month. When he first enlisted in the army he was only 16 years of age, and in his 21st year when he was retired.

THOMAS BARTHELEMY CARDON.

Extracted from History of Utah: Comprising Preliminary Chapters on the Previous History by Orson Ferguson Whitney (1904)

A soldier of the Union in the Civil War, and for many years a prominent citizen of Logan, T. B. Cardon was by birth an Italian, the exact place and date of his nativity being Brae, Prarustin, Piedmont, August 28, 1842. His parents were Phillippe and Martha Maria Tourn Cardon. Their ancestors were of the Vadois or Waldenses, and among the remnant of that people who were driven from Switzerland by the Church of Rome about the beginning of the eighteenth century. They were in comfortable circumstances, owning the home they occupied and the small farm and vineyard they cultivated. When not thus employed they were engaged in silk culture. The father was also a builder. As a boy Thomas assisted him in the vineyard and also as a mason and carpenter. A few short winter terms in a common school, where French and Italian were taught, comprised his earliest education. He was an artist by instinct, possessing a refined soul, and the world was to him an open book, in which he read deeper and loftier lessons then those taught in the schools.

Up to the age of twelve he remained in his native land, where, in 1852, his father and mother, himself, four of his brothers and two sisters joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Two years later the family emigrated to Utah, sailing from Italy in January and coming by way of New Orleans to Kansas City, whence they traveled overland to Salt Lake City, arriving here late in October. .Tabez Woodard had charge of their company on the sea, and R. L. Campbell on the plains. Many were afflicted with the cholera, among them Thomas and one of his sisters. They settled first at Mariottsville, near Ogden, whence they went south in the move of 1858 and afterwards returned to Weber county.

Thomas, then a boy of sixteen, after assisting his father’s family to return, visited Camp Floyd for the purpose of obtaining employment. Ambitious for an education, and being told by some of his countrymen at the post that if he enlisted he would have the privilege of attending the camp school

free, he joined the army and became bugler in Company “G,” United States Tenth Infantry. He learned

the English language from a comrade, who, like himself, spoke French, and having an inherent love

for culture, pursued his studies alone, acquiring by diligence a fund of useful knowledge.

Weary of camp life, he applied in I860 for his discharge, but before it reached him the Civil War broke out. Here was activity, the thing he desired, and he now withdrew his application and started with his company for the East. The founder of Camp Floyd, General A. S. Johnston, and some of his troops, espoused the Confederate cause, but the company with which T. B. Cardon was connected proceeded to Washington, D. C., and joined the Union forces. On March 10, 1862, his regiment was called into active service, and he was at the headquarters of General McLellan, commander of the Army of the Potomac, from the opening of the campaign that year until after the battle of Malvern Hill. He was in the battles of Big Bethel, Yorktown, Williamsbury, Gaines Hill, Fair Oaks, and the famous Seven Days Fight before Richmond.

On the second day of the last named engagement, June 27, 1862, he was seriously wounded in the left arm and side. While he was being borne from the field in the arms of two comrades, one of them had a leg torn away by the explosion of a bombshell and the other was killed by a rifle ball from one of the enemy’s sharpshooters. It was not designed, however, that Thomas B. Cardon should perish on the field of battle. Though carried to the hospital and placed in the charnel house with those who had died of their wounds—for he was apparently lifeless and was reported dead —he revived next morning about daybreak and succeeded in rejoining his brigade, after being hotly pursued by the enemy’s pickets. His wounds healed in time, but he was rendered incapable of further service, and on February 2, 1863, was honorably discharged. For his services in defense of the Union he was afterwards granted a pension of ten dollars a month, which he drew as long as he lived.

From the convalescent camp near Alexandria, he proceeded to Washington, where he remained a month, and then visited York, Pennsylvania, where he learned the art of photography. He next moved to Harrisburg, where he obtained a situation and worked at his profession, subsequently opening an art gallery. In 1865 he went to Nebraska, settling in Nebraska City, and in 1867 rejoined his relatives in Utah. They were then living at Logan.

There he established an art gallery, carried on the photographer’s business, and also opened a watch making and jewelry establishment, the first one in that city. He was successful in business for many years, when reverses came, and his fortune was swept away. On November 13, 1871, he married Lucy Smith, daughter of Bishop Thomas X. Smith of Logan, and sister to Orson Smith, ex-president of the Cache Stake of Zion. She bore to him eleven children. Mr. Cardon had two other wives, one of whom has five children.

He held various public positions in Logan. He served nine years as city recorder, and in 1882 and in 1884 was elected an alderman and sat in the city council. In 1886 he was again nominated for that office but declined the honor. At the time of his death, he was city auditor. In all positions of trust, he exhibited not only skill and ability but steadfast honesty of purpose.

To his religion he was true as steel. As a home missionary of Cache stake, and an assistant superintendent of the Sabbath schools of Logan he labored with honor to himself and with helpfulness to those with whom he came in contact. Throughout his life his convictions and sentiments were pure and exalted. He held successively the offices of Elder and Seventy, being ordained to the former in 1870, and to the latter in 1884. He was president of the Second quorum of Elders, and one of the presidency of the Sixty-fourth quorum of Seventies. He died at his home in Logan, February 15, 1898. Beloved in life, in death he was widely and sincerely mourned.

T. B. Cardon Dead.

Passing Away of One of Logan’s Most Highly Respected Citizens.

The hand of death has again been thrust into our midst, and has plucked from amongst us one whom, not only his family, but the entire community, will miss and mourn for. Thomas B. Cardon passed away at his home on Tuesday evening after an illness which began as (unreadable) and reached its culmination in an attack of pneumonia which developed recently and was the stated cause of death.

Nervous prostration, brought on by worry over business reverses which a less honest man than he would not have noticed, which had weakened his body and made it an easy prey to disease, was the real cause of death.

He built up a magnificent business here, and then when the panic came a few years ago he lost it all, simply because he gave every man the credit for being as honest as he was himself. He never recovered from the shock of the affair but fell prey to needless worry; for no man in Logan would have deemed Thomas B. Cardon’s word less than his bond. But the strain was too great; the magnificent brain wore itself out and the big, honest heart of Thomas B. Cardon was stilled forever.

He leaves a wife and family behind him; who will miss him as much, but will treasure within their hearts the memory of his worth and goodness.

A biographical sketch of Mr. Cardon was partly prepared for this issue, but was withheld at the request of relatives, in order to obtain some additional information in regard to his life.

The funeral services will be held at one o’clock on Friday, in the tabernacle.

-Published in the Utah Journal Newspaper, February 17, 1898

MAJOR CARDON’S CAREER.

__________

Served During the War and Was a Useful Citizen.

Logan, Feb. 16.-Mr. T. B. Cardon, who passed away last evening, was a native of Italy, 56 years of age. He emigrated to this country when but a small boy. He enlisted in company G, Tenth United States infantry, at Camp Floyd, in 1858, as bugler, when but 16 years of age, and served until Feb. 2, 1863, when he was honorably discharged, having been wounded and disabled in the seven days’ fight before Richmond. He also participated in the battles of Big Bethel, Fair Oaks and the capture of Yorktown. He established the first watchmaking and jewelry establishment in northern Utah, and for the past quarter of a century has been prominently identified with the building up of Cache County. He was a loyal Democrat and very popular here, running 150 ahead of the Democratic ticket, upon which he was a candidate for city auditor last fall. The funeral services will be held in the tabernacle at 1 o’clock on Friday next.

– Published in The Salt Lake Herald, 17 Feb 1898, Thu, Page 7.

THE DEATH OF T. B. CARDON.

__________

He was a Patriotic Soldier and an Upright Citizen.

Correspondence Tribune.

Logan, Feb. 16.-Universal sorrow is expressed over the death of City Auditor T. B. Cardon, who was a general favorite in the community. Mr. Cardon’s life was an eventful one. Coming from Italy, his native land, in compay with his parents, at an early age, he landed in Salt Lake in 1854. When but 16 years old he enlisted at Camp Floyd in company G, U. S. Infantry, as a bugler, in order to obtain an education. He had applied for his discharge just when the war of the Rebellion broke out. On hearing the news, he withdrew his application and went to the front. He served during the war and was engaged in many battles, among them Fair Oaks and Big Bethel. In the “Seven Days’ Battle” before Richmond, he was so severely wounded in the arm and side by a musket ball that he was carried from the field for dead. After the war he returned to Utah, locating in Logan in the sixties. Here he built up a large business as a jeweler. He failed a few years ago, and although his obligations were discharged in an honorable manner, his failure was a continual source of worry to his super-sensitive organization, and caused nervous prostration, which rendered him too feeble to resist the attack of pneumonia, which was the immediate cause of death. Funeral services over his remains will be held in the Tabernacle on Friday afternoon, and it is safe to assume that it will be crowded. The City Council will meet tonight, pass resolutions of respect and arrange to attend in a body.

-Published in The Salt Lake Tribune, 17 Feb 1898, Thu, Page 7.

Funeral of Major Cardon – Report From Teton Basin.

Logan, Feb. 19.-There was a big attendance at the funeral of T. B. Cardon yesterday, the tabernacel being filled, and more genuine sympathy and sorrow was evinced over the death of Mr. Cardon than over any one who has died here for years. The floral offerings were beautiful. Elders Moses Thatcher, F. W. Hurst, C. D. Fjeldsted, L. R. Martineau, Isaac Smith, Orson Smith and Bishop Thomas X. Smith were the speakers. all the city officers attended, and in a body followed the remains to the grave. Judge C. H. Hart was one of the pall bearers.

-Published in The Salt Lake Herald, 20 Feb 1898, Sun, Page 7

MAJOR CARDON’S MORTGAGE

__________

Friends of the Deceased Raise $1,794

-Logan Notes.

Logan, Feb. 23.-When Major T. B. Cardon died recently he left a mortgage of $1794.40 on his property here. Some of Mr. Cardon’s friends, who knew of his financial embarrassment, worry over which was the main cause of his death, started a subscription to help lift the mortgage. This morning Mr. S. A. Langton, who has had charge of the matter, announced that he had succeeded in raising $1,794.50, or 10 cents more than the amount of the mortgage. It is undoubtedly the largest amount ever raised here for an individual by subscription, and is another tribute to the popularity of Mr. Cardon and the sympathy felt for his family.

-Published in The Salt Lake Herald, 24 Feb 1898, Thu, Page 7.

History of Tommy Gordon

(Thomas B. Cardon), Bugler,

Co. G, U.S. Infantry

by A. F. Cardon

The Cardons are said to have originated in a little village called Cardonna near Barcelona, Spain. Whether that is so, or whether the place of origin was in France, near Lyons, will perhaps never be known. Nor does it matter. The date, if in Spain, was likely prior to 1,000 A.D. From some sources we gather that the Cardons were Spaniards who spread into France, Belgium, Germany and Italy. But the Cardons closest to being identified as our ancestors are those who were near Lyons, France, where they became disciples of Peter Waldo (1170), known as Waldensians.

Peter Waldo, a wealthy merchant of France at Lyons, had apparently been reading his Bible, in particular Luke 18:22. According to that account, “a certain ruler” had asked Jesus what he should do to inherit eternal life. Jesus recited several of the Ten Commandments. The ruler said he had kept them from his youth. When Jesus learned how faithfully the ruler had followed the Hebrew Commandments, He added “Yet lackest thou one thing; sell all that thou hast, and distribute unto the poor, and thou shalt have treasures in Heaven; and come, follow me.”

Peter was so impressed upon reading this admonition that he resolved to follow it; he disposed of all his treasure, either by selling it or giving it directly to the poor, and then went among the people, preaching whatever he felt was right to conform to the teachings of the Master. Many people believed his teachings, some of the more ardent ones desiring also to go among the poor with this new doctrine of simplicity, obedience to the moral codes of the early Christians, and faithful obedience to Jesus. Waldo had the New Testament translated into Provencal; and the French Pasteurs, with such an aid, traveled among the people, preaching what he had been saying and what Christ had proclaimed throughout the shores of Galilee and the hills and temples of Jerusalem. That brought upon the heads the Waldensians the wrath of the Pope.

Peter paid the Catholic priests little heed, continuing to preach to the poor about simplicity and being free, being content to live humbly, walking the straight and narrow path, and being unmindful of the things inflicted upon by them by the Roman Church. Since Peter, after seven or eight years, remained steadfast in his quaint views, the Pope excommunicated him.

The many forms of discipline directed against the Waldensians over the ensuing years were so severe that they departed Lyons, some going north of the Alps and some to Lombardy. In due time, another body of Waldo’s converts escaped the ire of the Catholics by settling in the remote valleys along the eastern slope of the high and rugged Alps. They became known as Vaudois, still speaking French and practicing what Waldo had preached many years before; they toiled out an existence in the lands bordering the Pelice, the Angrogne and the Clusone rivers, and mounting the slopes of the Alps.

Their beliefs did not bring them peace in religious nor civil matters. They were regarded as a thorn in the side of the rulers of the Savoy. Even Louis XIV, helped by an Irish Brigade that didn’t like Cromwell and crossed the channel to France, sent soldiers against the odd people. Then Cromwell stirred up so much sympathy for the Vaudois that the English gave them a subsidy and Milton wrote this sonnet about their sad lot:

ON THE LATE MASSACHER IN PIEMONT

Avenge, O Lord, Thy slaughtered Saints, whose bones

Lie scatter’d on the Alpine mountains cold

Ev’n them who kept thy truth so pure of old

When all our fathers worshipp’d Stocks and Stones

Forget not: in they book record their groanes

Who were thy sheep and in their antient Fold

Slay’n by the bloody Piemontese that roll’d

Mother with Infant down the rocks. Their moans

The Vales redoubl’d to the Hills, and they

To Heav’n. Their martyr’d blood and ashes sow

O’re all the Italian fields where still doth sway

The triple Tyrant; that from these may grow

A hunder’d fold, who having learnt thy way

Early may fly the Babylonian wo.

– Milton

At the time of the French Revolution the English stopped paying the Vaudois a subsidy, but Naploeon, great hearted as usual, paid them one from his own coffers. But it didn’t fasten a peace on the luckless people, only a form of turmoil. After Napoleon fell for the last time, an Englishman, visiting the Vaudois, wrote feelingly about them. There followed an upsurge of compassion for the people, augmented by funds sufficient to establish much needed schools and churches. One English Colonel, who had lost a leg in war, devoted himself so unselfishly to the Vaudois cause that no fewer than 120 schools were established. Not only that; he had the Italian language replace French language in the churches which may have been his way of getting back at Napoleon.

By this time, the Nineteenth Century was well on its way. In 1801, my grandfather, Phillippe Cardon, was born. He lived until he was over 88 years old, long enough for the Cardons in Cache Valley to know him. In 1842, my father, Thomas Bartholomie Cardon, was born. Both of these births and seven previous to 1842 came to the Cardon family of that age in the little village of Cardon, high in the Alps from Prarustin, close to Pignerolo, in Northwest Italy.

In the middle of the Nineteenth Century, a new era opened for the Vaudois. It brought for the Cardon family a reawakening of the Waldo spirit. A missionary named Lorenzo Snow came to the Alpian valleys, preaching that the message of Christ had been lost to the world for many centuries, but was now restored to Joseph Smith, jr., a prophet of God. The Lord, advised Lorenzo Snow, wanted the Vaudois to adopt this message which denied the Roman Catholic Church to be the true church bearing the gospel of the Savior, and advocated a return to the simplicity of the early church.

The good people around Prarustin listened with close attention to Lorenzo and his fellow missionaries. One can imagine their astonishing reflections:

Weren’t these messages but the echoes of Peter Waldo’s voice, coming through the 700 years since that good man spoke? Even though we are hidden in these high mountains, we suffer persecutions; then why linger here when we can go to the Rocky Mountains and be free from these evils, have lands for ourselves, even in abundance, and be blessed by the same good Lord?

Among those who listened eagerly was the group living at Cardon village, at the end of the trail leading away from San Barthelemie. A descendant of those people visited Cardon 85 years after the time the first missionaries brought them the message of Joseph Smith, jr., who wrote:

…we went into the simple Waldensian church – (Leah was given one of the old hymn books). – After a bite to eat we started for the villages following old trails hundreds of years old, – on foot, of course, for there were no roads. We left our tiny car at the Pasteur’s house.

It is a beautiful country, green with woods and grassy slopes and colored by many wild, brilliant flowers, like poppies, pink scabiosa, wild red geraniums, blue flowers and yellow. The villages are tiny clusters of crude rock houses clinging to the slopes in clearings devoted to tiny patches of grain, potatoes or grape vines. Some villages have a dozen or more houses, some only three or four, a few only one or two. And the villages are widely scattered.

But the Pasteur who was accompanying as a guide said the Cardon village was still further on.

Leah said she saw disappointment flood my face. Had I come all this way only to be denied my goal?….So Leah and I, determined to see the village of Cardon, pressed on, guided by our new friend Rivoir who could understand some English, speak French and Italian and some Spanish…. Up and down, up and down, up some of the steepest trails. At times I could scarcely breathe, my head and heart pounding, my face purple!

At last we came to an old church, much older than the one at San Bartelemio which could have been (probably was) the one in which father worshipped as a boy. Under its floor were buried two German noblemen who came to the village as soldiers of the Duke of Savoy!

On up the hill another half hour of steep climbing – and we reached Cardon, a village of 12 families as high on the slopes as any in that valley. (Cardons were ever thus.)

But there were no Cardons today where they once thrived. Old homes are there….occupied by others…But I rather think father’s home stood on what is now only a foundation surrounding a neat garden.

And that was the way that Dr. Paul Vincent (P.V.) Cardon and his wife Leah found the birthplace of the Cardon family that left the Vaudois back in 1853. There is where Grandfather Cardon grew to be 14 years old by the time Napoleon fought the Battle of Waterloo. The record shows the family to have consisted of Cardons intermarried with Jahiers and Malans and Tourns running back to 1599; and all of them lived in the little villages almost within a stone’s throw of each other. Or course, the wives were wooed in the valleys of Rora, Tour, and Pramal, all within about 10 or 12 miles of Prarustin.

The conversion of some of those Cardons, along with others, was followed by departure from the Vaudois in 1853. To Liverpool and to America they traveled, accompanied by the 11 year old lad called Tommy, across the wide ocean, over the settled parts of the country to the Missouri, and thence across the plains by ox team, horse, mule or afoot, any way to get to their goal. After reaching Salt Lake City, only seven years after the first Mormons arrived there, they looked around for a place to settle, finally choosing Ogden’s Hole, later known as Five Points, north of Ogden. In time, some of the family went to Cache Valley, some stayed near Ogden and the women followed their husbands to Wyoming to establish ranches. They became part of the early settlers of Zion and played their several parts, some more, some less than was to be expected.

PART II – THE BUGLER OF COMPANY G

As for Tommy, the adventurous lad getting into halfway of his teens, he was looking for work; in fact, he might well have been taught and required to do so by the frugal ex-Vaudois. In 1858, like everyone else in the valleys of Utah of that time, Tommy heard of Johnston’s Army where work might be found in the setting up of Camp Flloyd, west of the Jordan river, not so far from the Point of the Mountain. Hearing that the installation wanted workers, Tommy left his family and made his way to the new site, seeking a job. In addition to finding what he went to get, he met a Frenchman named Eugene LeRoy.

His new friend was born in Marseilles, France, had left there for America and had in due time joined the Army. He was a clerk soldier, black hair, dark brown eyes, complexion dark and five feet five inches high, according to the records kept by Uncle Sam. He liked Tommy and Tommy liked him. The two made a pact to stick together and Tommy would learn to write and speak English, as taught by the solider clerk. LeRoy also taught Tommy the art of watchmaking.

Army records show Thomas Gordon, bugler, infantry, enlisted September 1, 1858, to serve five years. Born at Pignerolo, Italy, 15 years of age. 5 feet, 2.5 inches tall. Fair complexion, hazel eyes, brown hair. By occupation a laborer. Given discharge at Washington, D.C., on February 3, 1862. Character, “good”. There is a Surgeon’s Certificate of Discharge.

Copy in possession of Philip Cardon, Logan, Utah

Then Tommy, on September 1, 1858, enlisted in the United States Army and made his mark instead of writing his name. The Enlistment Officer understood Tommy to have pronounced CARDON as GORDON and so he entered Tommy’s name as such. That same officer thought Tommy gave his age as 15 but Tommy had turned 16 on August 28.

Yes, Tommy knew little English and was uneducated. Eugene LeRoy took him in charge and had him speaking and writing English in due time, as attested by the diaries. He was an inquisitive lad to whom the prospective soldier life, especially with his tutor on hand, was appealing. He would learn things he wanted to know and perhaps get opportunities to make something of himself. In the end, he got both, sometimes with regrets and sometimes with great satisfaction as we shall see.

His first recorded adventure was a log of the trip made by a squad of soldiers out of Camp Floyd, sent to the scene of the Mountain Meadow Massacre in 1857. The expedition started April 21, 1859, about six months after Tommy’s enlistment. He was along. Since he had hardly started to learn English, it couldn’t be expected that he would have a diary of the trip; but he did make notes of the marches, the distances traveled each day and the site of each camp. From these notes he made up the record shown on page 50.

But where Tommy failed, H.H. Bancroft succeeded. Of that trip, Bancroft, in his History of Utah, had the following to say after he had described the massacre:

It was not until nearly two years later that they were decently interred by a detachment of troops, sent for that purpose from Camp Floyd. On reaching Mountain Meadows, the men found skulls and bones scattered for the space of a mile around the ravine, whence they had been dragged by wild beasts. Nearly all of the bodies had been gnawed by wolves, so that few could be recognized, and their dismembered skeletons were bleached with long exposure. Many of the skulls were crushed in with the butt-ends of muskets or cleft with tomahawks; others were shattered by firearms, discharged close to the head. A few remnants of apparel, torn from the backs of women and children as they ran from the clutch of their pursuers, still fluttered among the bushes, and nearby were masses of human hair, matted and trodden in the mold.

After burying the remains as thus described, the soldiers proceeded to Santa Clara and then began the return trip May 16, taking 14 days to reach Camp Floyd.

Tommy was enrolled in Company G, 10th U.S. Infantry, later listed as Bugler. The soldiers he was with were the ones who had marched across the plains and mountains to put down the Utah “Rebellion” that proved to be such a fiasco. But it was time, in 1860, to disperse that army.

On March 7th, 1860, the Deseret News reported that General A.S. Johnston, Commanding Officer of that noted trip, had left Camp Floyd a few days before that date, on his way through California and the Isthmus of Panama, to Washington, D.C. The News said that there were many reports of the purpose of Johnston’s visit, “…but he unquestionably goes in strict obedience to orders.” Colonel Phillip St. George Cooke, the many who commanded the Mormon Battalion during its travels to San Diego in connection with the Mexican War, took over command at the camp.

According to the Deseret News of April 11, 1860, Secretary of War, John D. Floyd, for whom the camp was named, issued orders to reduce the camp’s military force to 3 companies of the 2nd Dragoons, 3 companies of the 4th Artillery and 4 companies of the 10th Infantry, Tommy’s outfit. Since the Cardon family has no record of Tommy having traveled with the forces transferred to other points and has a record of the 10th having gone into the Virginia Campaign of 1862, it can safely be assumed that our father remained at the camp until the remaining soldiers were transferred in 1861 to a point not far from Washington, D.C.

Bancroft said of this last move, in reviewing the events in Utah in 1860 “…about a year later, war between the North and South being almost a certainty, the remainder of the Army was ordered to the eastern states.”

By wagons, teams, horseback and afoot, the last troops of the Johnston’s Army, the forces of that meaningless expedition, gathered at a point not far from Washington, D.C. It is probably, though not demonstrable, that Tommy had been keeping some records which he referred to as his Journals; but his known journals are as diaries, the first entry being:

March 10, 1862: We start today for the other side of the river at 2 o’clock. A.M. Arr in camp at 7.

The exact location of this camp is not given in the diary but was, no doubt, near Alexandria. There the troops rested until March 15, during which time there was rain and waiting for orders. On that date, the soldiers moved to within 2 miles of Alexandria and then it really rained, according to Tommy, who wrote:

The camp was a perfect flood until morning; everybody was soaked to the skin all night. No one slept, for the tents could not protect us any. I was on guard and had to stay up all night.

Tommy caught cold, his eyes were sore, the rain continued and “most everybody was out in the woods making large fires to keep warm” The soldiers had little to eat and no coffee. Tommy went to Washington but was so sick that he could hardly make it back to camp. In the woods, he even walked into trees, his eyes were so bad.

This series of troubles for the Army near Alexandria ended March 25, when they “…got board the steam boat…in the stream all night.’ The stream was the Potomac River.

But even going down stream had its drawbacks. The steamboats swerved and “…we had to turn back & got two schooners…” to turn them around and get them going again downstream. Tommy wrote:

March 27th, 1862 Started at 10 o’clock kept on the Potomac all day. At about sunset came in sight of Chesapeake Bay. March 28th At sunrise we were right abreast New Point Comfort. Entered the harbor at Fortress Monroe at about 12 o’clock. Landed about (?) marched about 8 miles in the mist so thick that we could hardly see anything and no water but swamp water. Camped without coffee or anything else all night, the wagons not being able to reach us. In night a very strong cold wind arose. Some get up and build fire in the camp, others went in the woods and built them.

Tommy was sick and the weather was not doing him any good, no doubt treating at least some of the others in the same manner. But the men, laying over for a few days, sought entertainment, as Tommy reported:

March 31st: This was a beautiful day – the sun shone all day. 5 men of the company & I went down the beach after oysters. Met plenty oyster boats but no oysters until we came to a beautiful farm on the southwest side of Hampton Harbor. The ruins of a beautiful farmhouse stands there yet but no one lives there. Also, huge oyster beds, but no one to take them, only when the tide is very low, the soldiers go in up to their knees and get the smallest ones around the edge of the bed. The men enjoy themselves very much except me; I was too sick to do anything. I ate a few oysters – that was all I could do. The men I went with went in up to their waist & got some very large & fat ones, better than I ever saw in Washington & good many other places. We went away before the order came for monthly inspection and drill so we were absent from both. We expected to be confined as soon as we got home but the orderly sergeant was too good to report the men absent and the man that has charge of the bugler did not report me absent and the adjutant did not take notice so none of us were confined.

Of course, Tommy was sick, so he went on the sick report. But the weather improved greatly, the roads getting dusty for April 4 when the Brigade marched northward to Little Bethel. General George B. McClellan was getting ready to lay siege to Yorktown1 while Major General George B, McClellan directed the Peninsula campaign march to August 1862. The Brigade reached Big Bethel at noon on the 5th, according to Tommy’s report:

A negro who was there said that the rebels left there in the morning on the advance of the army. They were just about eating breakfast when they were surprised. They left everything as it was and only fired three shots out of some heavy guns they had there & then run. The Union troops captured six of their guns. We stopped there till about 3 o’clock to let the troops ahead of us go further & let those we past in the morning get past us again. We then marched about 3 miles further and came to some rebel barracks which we occupied for the night. Some of the quarters were full of hogs which the soldiers were not at all vext at for they had no meat of any kind for some time the most of them especially fresh pork. Not as long as long as they have been soldiering except, they bought it out of their own pockets & soldiers are not likely to do that. Great many of them had nothing to eat that day so they went right to work and killed a good many of them. There was some of the officers killed some themselves and others were putting the men in the guard house for it. They then drove them out in the woods and killed them there, but there were patrols sent out after them. They took some and others got away, even some of those they took got away from them as they were coming in with them.

Tommy further reported that April 6th saw a renewal of the pig slaughter because that was all they had a chance to eat until nearly night, when the wagons got in with pilot bread and coffee. Pilot bread is hard tack – a hard biscuit or loaf made from flour and water without salt, baked into a hard loaf. He was revived by the hog meat, coffee and bread and felt better than any day since he went to Washington and got sick.

The Brigade lay over for days except for the fatigue parties formed to build fortifications nearer to Yorktown. Tommy reported occasional picket firing and exchange of shots between the two forces but nothing of any consequence. Large siege guns were being brought up the river – the York – to help McClellan lay siege to the rebels in Yorktown. On the 11th, the Brigade got orders to lay-in a three day supply of rations. The diary for the 12th was as follows:

We started at nine o’clock and waded through the mud in the woods for about three and a half or four miles. We then came to a large field not far from York Town right in the bend of the river & camped. Orders were given by General McClellan not have any call of any kind; beat on the drum or sounded with the bugle trumpet or anything else. No noise of any kind no discharge of fire arms, &c. Serg’t Carroll and another man of the company went about a quarter of a mile from where were our pickets are from where they could see the rebel batteries and sentinels. They were told that on the night of the 11th they were fired into by the rebels and two of their number were killed and 2 or 3 horses also that 2 shells were fired where we are camped the place being occupied by some vols. without doing any harm only making them leave to go further back.

On the 14th:

An engagement took place between three gunboats and some rebel batteries on the other side of the river. One of the shells took effect on the rebel flag staff, cutting it in two, about the center, after which they fired five shots and stopped and the boats drifted down the river a little further.

While Tommy lay in camp he heard the reports of heavy firing, the engagements between gunboats and shore batteries, the calling out of fatigue parties and the occasional capture of a prisoner or two. This program continued until April 28 when Tommy reported:

Lay over warm and sunshine all day. At 5 o’clock in the evening my co. and another out of the 17th were called out under arms. Every man then got a shovel and in co. with two more cos. out of each battalion in the Brigade went out towards Yorktown. When we got within 700 yards of the rebels’ fortification we stopped behind some hills and woods. At about 8 the rebels began to throw shells among and around us. One man of the 4th Inf. got wounded in the thigh, it was thought mortally. At about 2 in the morning an officer came and ordered us to go to work on the fortification about 300 yards further, but when we got there we were ordered back again by the Chief Engineer who said that he had not sent for us, that if he wanted us he would send one of his own officers. We then went back and stopped there until 4 when we started for camp.

This sort of shilly-shallying folded around proceedings. The rebels threw shells into the Union forces and the Union forces answered with their 100-pound guns. These guns were heavier than the Rebels were used to, so they brought up heavier guns to make answer. More heavy guns were brought up for firing until the air was filled with the shells and the steamboat landing at Yorktown was reduced and Rebel batteries exploded. McClellan thought he was ready to take the town and the area between the York and James rivers, while General Jos. E. Johnston was preparing to withdraw from Yorktown as a result of a decision on the part of the Confederates that their position was not tenable. Off Fortress Monroe, the Monitor had defeated the Merrimac previous to the arrival of Tommy and his buddies in a great armada. The rains were making a quagmire of the countryside and the roads. Men were being run down and captured, whole regiments were surrendering, brigades were slushing through marshes trying to retreat and others were slushing forward to capture the fugitives. Men stopped to tell what they had seen, what they had been told was happening.

The tales differed very much. In the wild melee the real situation was lost. Tommy and his comrades heard only a word of the entire story; the rest of the fateful words were drowned in the thunder of the guns set in motion by the men back of the lines, far away.

The sweep of Confederates away from Yorktown as witnessed by Tommy was recorded as follows:

May 4th Half past four in the morning: Yorktown is ours. The brass bands are playing, bugles and drums are sounding and camp is a scene of rejoicing all over.

9 o’clock A.M. The following particulars about the taking of Yorktown are in camp: this morning at about 2 o’clock, General Smith made a charge on the Rebels’ works and took them so much by surprise that they could do nothing but run, leaving their arms stacked, cannons loaded and many were taken prisoner.

Wrote Bruce Catton in the Terrible Swift Sword, page 278:

Joe Johnston had gone, leaving empty trenches, a number of abandoned cannon, and a set of live shells with trip wires attached buried in the works to discourage Yankee patrols.

Tommy continues:

All their fortifications are full of torpedoes and nobody is allowed to go inside the works on account of them. It is also reported that the Rebel Irish Brigade laid down their arms and refused to fire for them (they were stationed at Yorktown) and that they began to evacuate Yorktown four days ago.

Immediately after the capture of Yorktown the gun boats came up the river and the Stars and Stripes hoisted on Gloucester Point. The boats continued up the river.

12 o’clock M. Heaving cannonading has been heard up the river for about one and a half hours. It is reported that the gun boats are shelling the woods where the Rebels are retreating.

6 o’clock P.M. The cannonading is still going on, prisoners are continually coming in.

12 o’clock at night It is raining, the cannonading is still continuing. The cavalry is called out.

The next day, wrote Tommy, there was still cannonading north of them. “Some cavalry men that just came in from where they are firing say the Rebels are completely hemmed in by our troops. Also that 8000 prisoners were taken, including those taken yesterday.” All day the cannons roared and Tommy hovered over his diary telling that “…a man from the battlefield says our troops took Williamsburg once but were driven back again.” He continued:

9 o’clock P.M. We have just received orders to start to reinforce the troops at Williamsburg, taking three days’ rations and everything else belonging to us.

15 minutes later Orders have just come for us to pitch our tents again and to go to sleep until one o’clock. All the companies have coffee made for the men before they go.

30 minutes later The distant booming of cannons is still heard but we are not ordered out yet and everybody is going to bed again. It has been raining all day and night.

So they didn’t go to reinforce Williamsburg, and the next evening according to a man from the field of action, there was no reason to go to that point because “…our forces are in possession”.

The following day, May 7, “…the latest intelligence…” from the battlefield was that McClellan came up with the enemy about three miles beyond Williamsburg and “…after a pretty severe skirmish with his rear put him to flight across the Chickahominy Creek.” In fact, for four days Tommy’s information, set down in the diary was all the conflict he had to endure. He was waiting to be called into battle, the battle whose guns roared like the cannonade he heard the first day he started to write.

Things took a new turn on the 9th. At 3 o’clock in the morning of that day, “we have just had reveille and are going to start at 5 A.M.” And that evening he wrote, “7 o’clock P.M. Have just arrived in camp after having marched all day in mud up to the knee most all day”. He continued:

We passed through Yorktown and from there to Williamsburg and from there about six miles further where we are now on the same road that General McClellan took pursuing the Rebels. The day was awfully warm and the men suffered very much from the want of water.

Tommy’s experiences during May 10 included: the same wading through water, the same trouble getting good water to drink, the same blistering of feet, Rebel prisoners on their way to Northern prisons, and a tramping of 10 miles. The march was for four miles only the next day, and when they stopped they found that McClellan had also stopped to establish his headquarters. So the marchers lay over May 12th to take on a supply of bread and other rations. As for the beef, a three days’ supply, it was left behind when the march was renewed because they had no transportation for it. The march, begun at 8 :30 A.M. of the 13th, took them 14 miles to Cumberland Landing on the Pomunkey River.

Tommy’s next entry lacked excitement:

May 14th Lay over. All the troops here, consisting of 40,000 were reviewed in the evening by the Secretary of State (sic). Along with him were McClellan and staff. They could not have a regular review on account that there was no room, but he rode in front of every battalion. As he came to the end they gave him three cheers while he was riding in front with his hat off. When he came to Syke’s Brigade of regular infantry General McClellan said, turning to the Secretary, “This is my brigade.”

With this pat on the head, Tommy and his comrades slept through the night with rain relentlessly pouring down. Next morning they waited, according to orders, to march at 8:30, then at one o’clock in the afternoon. But at noon orders came that they would not march at all that day. So they went to bed to listen to rain falling harder than ever, all night.

After another day’s lay over:

May 17th, 1862, We started at 9 A.M., arrived at the White House2 at 1 P.M. where we camped. The road from Cumberland Landing to here is lined with wagons and they cannot move on account of the mud. Even the troops sunk in the mud up to their knees most of the way here.

This condition of muddy roads and heavy rains became a factor in the Peninsula Campaign. McClellan didn’t need this condition thrust upon him as a means of slowing his campaign. His bent was delay, even without the rains and mud.

The evening of the next day – a warm and beautiful one – the companies drew four days’ rations and got orders “to cook all the meat we had”, for they would have to march on the morrow. “The reveille will be at 2 and march at five” in the morning!

And at five they started and at 11 they camped at Tunstall’s Station. The army was moving toward Richmond, but before going farther it lay over for the purpose, apparently, of forming Syke’s Brigade into a Division. “Artillery and cavalry with some infantry joined us. The 10th is now the 2nd Brigade…”

Tommy might have added that General Philip St. George Cooke, in command of McClellan’s cavalry, was his last commander at Camp Floyd; and that his first commander was one of President Davis’ right hand men, General Albert Sidney Johnston. But Bugler Tommy may have been totally ignorant of who all the big shots were.

On the move at 9 A.M. May 21st the troops marched 8 miles toward Gaines’s Mill, about 8 or 8 miles north of Richmond. After a seven mile march the next day they were near the north bank of the Chickahominy, a country soon to be wracked with guns and cannons of a mighty battle. The troops were allowed “a gill of whiskey to be issued to each soldier each day until further orders, but we have got none yet,” and he wrote that four days after the orders.

On the heels of the reported attempts by the Rebels to burn the bridge across the Chickahominy the troops moved to a point about a mile from the stream. The companies were so close to Richmond “…no calls were allowed to be sounded whatever”. But firing was heard off toward and north of Richmond, caused in part by the taking of the Richmond and Potomac Railroad, so Tommy was told. Then on the 28th he wrote:

We started from camp at sunrise, leaving all behind us with the exception of canteen, haversack and two days’ rations, leaving the cook and sick to guard them…we came to some troops that were engaged in yesterday’s action. Two of them told me the following:

“Yesterday we came to the railroad about a mile from here and took possession of it. We then placed two pieces of artillery on the track. Pretty soon a train came up and we fired into it, the train stopped and we tore up the track and run the train off. It was full of baggage and medicine. We took what we wanted and destroyed the rest. We then proceeded toward Richmond and found a bridge and destroyed it, placed some artillery along the road in some woods. Soon a large train came up full of soldiers going to reinforce Stonewall Jackson. We fired into and took them so by surprise that they immediately surrendered.”

Tommy’s informants said their troops were in full possession and that the captured men consisted of one brigade of infantry and one battery. Tommy and his buddies, in that day’s march, had reached Peake’s Station and the next day returned toward their camp near the Chickahominy. The sights along the road back were:

…there were many dead horses on the road and along side and unburied, which had been lying there for two or three days which caused rather disagreeable marching. The men are rather worn out, having had nothing but pilot bread to eat and bad water to drink with two days hard marching, but, still, they do not complain.

The troops had nothing else to do on the 30th than to meet a sudden thunder and lightning storm that came “down as if a thousand fire engines were playing at one place”. Everything got wet, the storm continuing until midnight. On the 31sat, with the Chickahominy rising rapidly because of the heavy storm, Tommy had to go on fatigue at two o’clock in the morning, accompanied by a company from each battalion, slowed down in their performance of duty by a rather unsuccessful search for tools to throw up embankments and build bridges to span the Chickahominy to the south.

We went to one bridge3 and were not needed so we had to turn back again the same road we came, when about halfway back we took another road4 leading to another bridge higher up the river.

We soon came in sight of the river and a large body of water covering the bottom land. We soon got to it and stuck in with good will, sinking into the mud and water at first only up to our knees, but got deeper and deeper until it was up to the waist.

After 20 minutes wading we came to a pontoon bridge which was not yet completed. After stopping there for about an hour, in which time the water raised 8 inches, flooding all the low lands, woods and plowed fields, we were ordered to go through the swamp to some timber lower down the river so that the batteries could fire across. We stuck in fully determined to do our best. For about 1,000 yards, we had to go through a newly plowed field where the water had just worked through to the surface. In this we sunk up to the knee, sometimes deeper. After this we struck the water, in which we went up to our waists, getting deeper and deeper until we had to swim, when we turned back again and took a more circuitous road; but this was worse than ever, it being full of ditches in which the men would go over their heads, but they soon became cautious and to look out for them and to jump them, but many of the men in attempting to jump would fall in and would have to be helped out.

In this way we proceeded, wading and swimming, until we came to an island about the center of the swamp5. Here we stacked our arms and rested. After a while an officer started toward the timber and waded until it got so deep that he had to swim when he saw at once that there was no need in making any more efforts, for the water was so deep, and very likely deeper, where the trees were as where he was. Consequently, we determined to make our way out of there as quickly as possible.

This was not so easily done as we though. But we started anyway, the nearest way to the hill. After wading out for some distance we became entangled in the weeds and the water became so deep that we could not wade any more. And there we were, could neither wade nor swim! The only thing left for us to do was to turn back, and even this was rather difficult on account of the weeds. We at last succeeded in getting back to the little island we had left, but which was almost flooded by the time we got to it again.

From here we took another direction for the much wished-for hill, which we reached after three hours of wearisome wading, swimming and pulling. Here we rested for about half an hour when we started for camp. From this hill we could see the Rebel pickets walking about from tree to tree on a hill across the river. The batteries opened fire, shelling the woods on the other side of the river to the great discomfort of the Rebels, who could not see any fun of it. The balloon Constitution was up all this time signaling to the batteries where to direct their fire.

So Tommy saw not only the famous Monitor but also this balloon which was the first to be used for spotting the enemy from the air.

While Tommy and his comrades were splashing, wading and swimming around in the waters near Chickahominy Creek on June 1, the battle of Seven Pines was coming to a close. It was in that battle that the Rebel command was also slushing around so clumsily that their attempt at annihilation of McClellan May 31 – June 1 was messed up.

During the night of that doleful June 1, orders came that the companies should start the next morning at six. But no troops moved then nor did they later. Facing a front 15 miles long, firing was constant. But for Tommy and his buddies, all they had to do June 2 was to drill twice a day, an order repeated daily for some time. As a diversion, an address by General McClellan was read June 3 to the troops, with General Sykes attending. General Sykes added to the address, when it was given to the 2nd Brigade: “Soldiers of the 2nd Brigade of Regulars, do you hear what your General says, ‘Trust in your General and he will trust in you.’ The Volunteers expect you to do whatever you undertake and so do I.” Tommy said, “It commenced raining about this time and continued all night.”

From the 4th and to 4 P.M. of the 13th Tommy wrote nothing of importance took place. Reports came in that many prisoners were being taken and dispatches advised that 10,000 of Beauregard’s troops with 15,000 stands of arms had been captured. It was during this period of idleness, it seemed, that Brigadier General J. E. B. Stuart, at General Lee’s orders, encircled the oncoming Union troops by riding with about 3000 cavalry forces from Ashland, Virginia, eastward to a point near McClellan’s headquarters at White House, then south to a point near the James River and then up that river to Richmond. Of course, as usual, Tommy and his comrades knew nothing of the ride at the time it was happening.

But at 4 P.M. of the 13th, when Stuart was ringing the Feds in that strange ride of 48 hours, Tommy was writing,

We just got orders to be ready to start at a moment’s notice. 5 minutes later. Got orders to fall in immediately with haversack, canteen and 3 days’ rations. 15 minutes later. The whole division is ready to go. This morning at about 4 very heavy firing was heard on our left but stopped again about 6:30. 5:30 P.M. We crossed swamp behind us about quarter of mile above Gaines’s Mills and are now in a line of battle alongside of it through the woods. 6 P.M. We are ordered back again to stack arms on the company’s grounds, not to take off our belts,….to fall in at a moment’s notice…take off their belts and go to bed…be ready to turn out at 3 o’clock A.M.

Tommy was north of the Chickahominy a mile or so near Gaines’s Mill. He could hear desultory firing but there was no general action pending the reorganization of the Confederate troops under their new commander, General R. E. Lee. And, too, it was a period of time when rain was an important factor to be considered, and Tommy’s diary shows the extent of that sort of weather. Rain, rain, rain.

On June 23 he wrote:

About 1 o’clock it began to thunder and lighten, continuing a perfect flash and roar until about two when the rain began to fall so fast that everything was immediately flooded and the water was running all over the camp like a river, though the camp is most all sand hills. It…continued very heavy all night.

The situation was scarcely changed for the next two days. But June 26 was a decided change for Tommy as though he felt the sudden sweep of battle, closer and closer.

6 A.M. It is reported that Stonewall Jackson is at our left with 35,000 men. (This report was not true. Jackson was on the way from the Shenandoah Valley, but to Lee’s chagrin, had not arrived. He was 12 hours late.) 10 A.M. Very heavy firing is going on our right. An order just came for us to pick up and stack arms and be ready to march with three days’ rations in a moment’s notice. Firing on our right is getting heavier and heavier all the time. 3 P.M. We just got orders to march immediately. The firing is heavier and heavier still, being a continuous roar of artillery all the time but here we go for it. 6:30 P.M. We are drawn up in line of battle in front of the enemy but have not yet participated in the fight. Expect to shortly. It is getting so dark that I cannot write any more. 12 P.M. Firing has ceased. No particulars are given with the exception that we are to remain on the field.

What was happening that day while Tommy stood practically, but not quite, under fire, was that General A. P. Hill impetuously attacked the Union forces north of the Chickahominy, not even waiting for the arrival of Jackson. He fought bravely but futilely. Later that day the famous Stonewall Jackson arrived before all was lost. Lee’s plan for General Jackson was to have him strike eastward at McClelland’s headquarters at White House and force him back from the northern position. Having done this, with McClellan falling back, the Rebel forces would drive him to ground.

Even though Tommy had made entry at midnight in his diary, he was up at 3 A.M. of the 27th of June and was ready to march at 5 only to find the troops retreating.

…Firing has commenced again, and we are retreating, but we are giving it to them hot and heavy. 10 A.M. We are now about three miles from Gaines Mills in an open field and are ordered to put our knapsacks in the wagons and ready for immediate action. 12 M. The shell and grape shot are coming into us like hail.

Three hours later Tommy was wounded. On the 28th day of June 1862, his diary continued:

I was wounded about 3 P.M. yesterday, keeping me from writing anything just then. A minnie rifle ball, that is the kind but a good deal longer, went through my (left) elbow and came out a little above my wrist and went in my side. Green and Vollmer of my company conducted me to the hospital a mile from the battlefield, where I was left until this morning, when the Rebels came in sight and there being no one to protect it, we had to leave without transportation. I am now at Savage’s Station, eight miles from where I started. My wounds are not dressed yet; they nearly drive me crazy.

So while Lee was gambling on Jackson and A. P. Hill turning McClellan’s right flank, Tommy got wounded and had to flee from his hospital, toward Rebel forces coming around that flank, and crossing the Chickahominy to be with his retreating army.

At Savage’s Station, where Tommy was, Lee brought on a battle again. McClellan was fighting a rear guard action and doing fairly well on the 29th. McClellan was not being drowned in White Oak swamp, much to Lee’s disappointment. But Tommy had a set of problems that took his mind off battles and centered them on his wounds and his desire to reach City Point, McClellan’s goal. Wrote Tommy:

We have just been told to start for City Point if we don’t want to be taken prisoners, but there is no transportation of any kind to be got. Here goes; I will try it anyhow before I will stop here and be taken prisoner. There is about 500 or 600 men here; most of the doctors have left.

Evening. I am worn out; my wounds drive me crazy. Oh, why do I suffer thus? I have marched all day in water and mud almost to my knees. I am completely worn out; and the enemy is only about half a mile from here. They tell me that I have taken the wrong road and I am almost among the enemy; that I will have to go back and take the right road and go to City Point yet tonight. What shall I do! It is getting dark. Oh, if I was only well! Oh, my arm and side! My clothes are saturated with my blood. I have not eaten anything for three days. I feel fait. Oh, my God, deliver me!

I am now at a little house some distance from the road. Mrs. Stockton, Col. Stockton’s wife, is dressing my wounds and bathing them with cold water. She also gave me a cup of tea- the first I have had for six months.

Dark. I have had to start again. I feel a little better, but O! how tired and weak from the loss of blood and having eaten nothing, not even a cup of tea or coffee, for so long until now. They say it is 11 or 12 miles to City Point yet, but it must be done, or stay and be taken prisoner.

No longer is Tommy concerned about the heavy cannonading, even though it is not far off. He ignored the battles, although they were so vital for either side. Like any wounded man scarcely able to stand erect, he felt for himself, alone. City Point only would satisfy him.

In the meantime, General Lee on the afternoon of June 30 launched an unsuccessful attack against the Union forces at Glendale (Fraser’s Farm) and followed that fighting with another attack the next day. The Union forces held as they gathered to City Point. Lee, failing in his final effort of the day, returned to Richmond. McClellan’s army reached City Point on the James River, the Peninsula Campaign a dismal failure.

Tommy, it might be said, was fighting or fleeing through all the Seven Days battle, carrying with him his wounds and spilled blood. On the 30th he wrote:

2 o’clock in the morning. I am almost dead. I have marched all day and night. I have often wished that I had been killed on the battlefield rather than suffer as much as I do, but God’s will be done, not mine. I am now in a wheat field alongside of the road to City Point. I am completely worn out. I must lie down and try to sleep. I have not slept any for four days and nights. There is only another man with me. He says he is sick, but I do not believe him. I believe he is afraid.

That’s what’s the matter.

Sun rise. The man with me has made a cup of tea for me. It is very good. I feel a little refreshed after having slept a little and partaken of some tea. Whatever this man may be I think he is very kind and I hope he may never suffer as I do.

Yesterday and last night there were so many ambulances going along, all empty. I tried to get into some of them but could not.

7 o’clock. I am now at a large farmhouse about one and a half miles from City Point. There are about ten or 12 negroes of all descriptions running about here making faces at the soldiers. There is one kept at work drawing water for the wounded soldiers as they pass. The water is very good. Some men coming from the Point say that the boat is ready to start. I must hurry.

9 o’clock. I am now a few hundred yards from the landing. There is a guard here who has orders to let nobody pass except the wounded but through some mistake they are keeping everybody out.

12 o’clock. Here comes an order to let you pass (that is, all the wounded) The surgeon is sending some back; their wounds are not bad enough, and I am afraid mine are not. That is, he may not think so. But here I am at the gates, and the surgeon, instead of turning his back, as I thought he would, looks at me with a sympathetic look and turns to two of the guards and tells them to conduct me to the boat.

I now see why some are turned back. There are some who are not wounded at all and are trying to make him believe that they are, but he cannot see it and sends them back. There was one right in front of me that to see him anyone would think that he had had his arm taken off by a shell, but there is nothing the matter with him, only a buckshot touched the back of his hand. Such men ought t to be out in front of the army and made to fight whether or not.

On the boat. There are about 500 or 600 aboard, all wounded with the exception of a few who only pretend to be. There are about six or seven other gunboats around with the Monitor besides this one.

1 o’clock P.M. We are about to start. There is another boat along with us to escort us some distance down the river on account that some of the boats were fired into yesterday by Rebel batteries on the opposite side of the river.

About 2 o’clock. We have passed City Point and all danger and the gun boat that came with us is returning.

Evening. Some salt pork and pilot bread has been thrown about the decks for the men to eat; not half as decent as a farmer would feed his hogs. I just gave 25 cents for half a pint of tea without sugar but it is better than none at all and I hope will keep life until I can get something to eat and drink.

It would seem that Tommy’s tribulations would have been assuaged, his wounds dressed, his stomach fed. But floating, or steaming down the James River alone could not fulfill his hopes. His wounds were minor, no doubt, but what he had gone through from June 27 to July 1 aggravated their seriousness. He continued:

July 1. If I do not get relief soon I shall not last long. Last night was another sleepless night for me, the boat being so crowded I could not find a place to lie down or sit and had no water to bathe my wounds. My arm and side are all black and swollen to three times their size. My clothes are stiff upon me, the blood being dry. Oh, that I were dead! I have not eaten or slept any for five nights and days. I feel very weak. At about twelve last night we came to Newport News and I was hoping we would disembark and go to a hospital, but after staying there for some time we started again for this place, Fortress Monroe, where we arrived about two o’clock this morning. It is now about half past five o’clock and we are about to land.

6 o’clock. I am now lying in the shade of a large tree inside the fort. A cup of good coffee and a piece of fresh bread has just been brought to me, the first I have had for about four months. It tastes very good. There is a very nice little surgeon who is very busy dressing wounds and I hope he will soon come to me. Here he comes now. I am afraid he will want to amputate my arm….the surgeon tells me my arm will have to be amputated. Oh God, have pity on me for I would rather die than lose my arm. I tell him I would rather die and he shakes his head and says that I may save it yet if I keep it constantly bathed in cold water and that is shall be saved if possible. I thank him kindly and he dresses it carefully.

10 o’clock. I feel a great deal better after having my wounds dressed and bathed in cold water for some time and having partaken of some refreshments, but we have to start for the boat again and go to Newport News, about 10 miles from here. Oh, well, it is not very far.

The almost hourly account of Tommy’s war was at an end. He was under actual fire June 29 for only a few hours when he suffered the shot that put him out of the war in due time. But he was surrounded by events that moved the pulses of the nation: the heavy cannonading, the twisted travails of the Confederate command, the futile fumbling of the Union command sluggishly prodding toward Richmond, the Monitor pounding the Merrimac (later, the Virginia), J.E.B. Stuart riding around the enemy’s army. General Robert E. Lee writing his name on the hearts of the nation that finally emerged. When Tommy reached Fortress Monroe he had learned the language and the demands of army life and had shown himself prepared to fulfill in full the oath taken in 1858.

At this point, the Vaudois lad, not yet 20, had virtually met the fire of his new land. His wounds might well have been fatal in view of the cruel flight he had to make from the field of battle to the rescue ship. Even on that ship, perhaps like many other young soldiers, he strove for the attention to his wounds that might very well mean life.