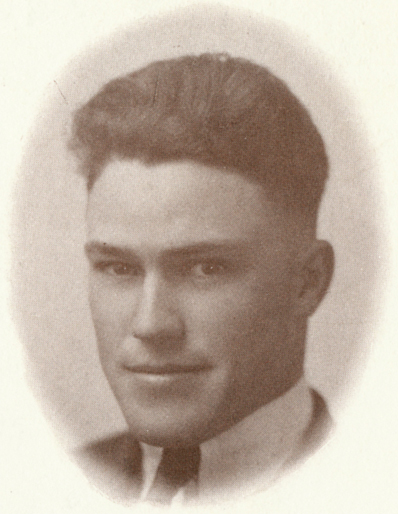

10 Aug 1901 – 11 May 1988

Great-grandson of Philip Cardon and Martha Marie Tourn

Grandson of Louis Philip Cardon and Susette Stalé

Son of Louis Paul Cardon and Ellen Clymena Sanders

CHARLES REDD CENTER FOR WESTERN STUDIES

BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY

LDS POLYGAMY ORAL HISTORY PROJECT

LOUIS S. CARDON

interviewed

by

Kimberly James

October 8, 1981

CRC-K151

Copyright 1982 Charles Redd Center for Western Studies

PREFACE

This is a transcription of an interview conducted for the Oral History Program of the Charles Redd Center for Western Studies at Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

Scholars are welcome to use short excerpts from this manuscript without obtaining permission as long as proper credit is given to the interviewee, interviewer, and the Charles Redd Center for Western Studies and other sponsoring institutions, if any. Scholars must, however, obtain permission from the Charles Redd Center for Western Studies before using extensive quotations of the manuscript or related materials.

The original recording was only the first stage in the creation of this manuscript. The audio tape was transcribed verbatim, and the manuscript was then edited to conform to the standards of the written language. An edited copy was returned to the interviewee for his/her corrections, additions, and deletions, which in some cases might have been extensive. This bound copy includes the changes made by the editor and the interviewee. In addition to this transcript, the original tape is available for scholarly use.

Beyond the interviewer’s efforts to obtain the truth during the interview, the Charles Redd Center assumes no responsibility for the accuracy of the statements made in this transcript. This transcript and tape may only be reproduced by the Charles Redd Center for Western Studies.

CHARLES REDD CENTER FOR WESTERN STUDIES

BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY

LDS POLYGAMY ORAL HISTORY PROJECT

INTERVIEWEE: LOUS S. CARDON

INTERVIEWER: Kimberly James

DATE: October 8, 1981

PLACE: Orem, Utah

SUBJECT: Life in a LDS polygamous family

KJ: This is an interview with Louis S. Cardon for the Charles Redd Center for Western Studies LDS Polygamy Oral History Project by Kimberly James at his home in Orem, Utah on October 8, 1981. The time is 7:00 p.m. Also present is his wife, Sister Winnafred Cardon.

LC: I was born on August 10, 1901 in Colonia Dublán, Chihuahua, Mexico. This was about fifteen miles from Juarez where the stake offices were for the Church.

My father had been teaching in Arizona at Taylor. He had been called by President Wilford Woodruff to go on a foreign mission. My father and mother were both teaching, and the Authorities changed that and told them to down to Mexico to teach. They were to help with the schools in Mexico in the Colonies. So they both went down, and they both taught the same as when they were in Taylor.

My mother was my father’s first wife. Her name was Ellen Sanders. My father’s second wife was Edith Done. She was also a graduate from a college in Payson, Utah, so she taught at times.

My father was principal of the schools. He would teach in the wintertime, and then in the summertime he would do survey work for Don Luis Terases who had a ranch said to be the size of New Mexico and Arizona together.

When the colonists got there, they had to get water out on their farm lands. They built their houses close together where everybody could be in a community, and they lived in the boundaries of the town. They had their church building which was also used for their school building. Their farms were all lying outside of town.

They would go out to the farms in different directions. My father did the surveying for the canals that brought the water out from reservoirs to their lands and also for irrigation of the town lots. At that time it was vital to them.

I was born there, and I was about ten years old when we left there. I remember that my father had a house built by a carpenter named Bluth with the help of my Aunt Edith’s father, Brother Done. It was a big house. It was the biggest house in town. Of course, my father had a big family or was expecting one. I remember in that big house there were six bedrooms with closets. a library, a bath and a screened porch upstairs. Downstairs there was a large entrance room or hall with entrances from the north and west sides of the house. A front porch was on the north and the west sides of the house also. There were also five rooms, a kitchen, pantry and a bath.

The dining room was an extra large room where they all ate together for a while. This was when the families only had two or three children. When I was born. I was the fourth child in Ellen Sander’s family. It was the oldest family, so neither of the other families would have that many. But there were quite a few when all three families got together.

I don’t think that worked out. I don’t remember. I know that this was kind of the hope. It did work out that they got a house for each family. This was after they had lived together in this house. I don’t know where they lived before I came. When I was old enough to remember, we had a library upstairs. I slept in the library. The others had houses.

They didn’t have water facilities down there generally. We had a big tank where we had water in the house. We had running water. The other houses in the neighborhood didn’t have it.

One thing that I remember when I was very young was that a Brother Tanner was head of the church schools. He would come down and stay at our place when he came to visit. One night he was sleeping in the room that I was in. It didn’t happen to be the library this time. In the nighttime I heard a noise, and it frightened me very much. I went over and got in bed with Brother Tanner. He calmed me down. and I got back into my own bed and stayed. A little while later I heard a noise again. It was really frightening me. I got in with Brother Tanner. The third time this happened I stayed in bed, and I discovered that it was Brother Tanner snoring that was disturbing me. But he was awful good to me.

I remember going to Aunt Edith’s house and to Aunt Irene’s. Irene Pratt was the third wife. My father would usually stay one night at one place, and he went to each family and spent one night at a time. He would just rotate. I was the oldest boy, and of course, I worked on the farms. I would go with him frequently to the other families so as to be ready to go with him when we went to the fields.

In Mexico I remember that my mother had asthma. She couldn’t stay in Dublán in certain times of the year. She would have to go to another community like Diaz. She taught in Diaz and she taught in Juarez at different times. Being young children, we went with her wherever she went. So there were times when there would just be Aunt Irene and Aunt Edith at home with their families.

After we came out of Mexico, we settled in Jamestown right near Tucson, Arizona. We had all three families there, although in different houses. There was some concern about having the polygamous families. The people from Mexico that settled in Jamestown were having some trouble with getting the monies to operate the land that had been allocated to them which was really submarginal land and it didn’t work out. They never were able to get water in sufficient amounts.

Later we went to Binghampton near Tucson when I was older. My mother would go off to other towns in Arizona to teach. I stayed with the other families to be on the farm. I would stay with one family for a few months and a few months with the other family. Aunt Edith and Aunt Irene were both just really good to me. In fact, the thing that I remembered, and it didn’t work so well with the other children, was they would treat me like they treated my father. I would get a little extra because I was working. I would get a little more rice pudding or something like this when anything was short or I would get a little better piece of chicken. They were really considerate. I didn’t realize it at the time, but I am sure that they felt for me being away from my mother. I was the only one of my mother’s children that stayed with them on the farm. They really made it as nice as it could be. I came to love them both very much. They did very many things for me.

While living on the farm, my father was often engaged in getting work for the men of the community such as a fencing job on a large cattle ranch that took several weeks to do. The men in the community would take jobs that would bring in money other than just what we could raise. We hadn’t got started yet with raising very much. I happened to be old enough to be doing the farm work mostly. We would put in quite an area of peas. I would take the peas to town to sell them to the grocery stores to get some money for our needs.

Then we finally got cows. We got a cash crop from them. We milked the cows. The boys were in Aunt Irene’s family, and Aunt Edith’s family were girls mainly. In the dairy business there was always the cooling of the milk and the taking care of it this way. The girls took care of that, and the boys did the milking part. They all worked hard because we were on submarginal land all the time.

We had so many things to contend with. We didn’t have water, so we would have to go down on the river. It was a little drive. We would dig down into the river, get the water down there, put it into a barrels and haul it out to the fruit trees. We would get them to live that way for awhile. Then the jackrabbits would peel the bark off the trees, so we had to put little chicken wire fences around each tree. Then the ants carne. In one night a bed of ants would strip every leaf off a peach tree. They did this several times. We had quite a struggle which eventually had to be given up. It just couldn’t work that way.

In all this working there, I enjoyed living with my brothers and sisters of Aunt Edith’s and Aunt Irene’s families. Many people speak of them as being half brothers and half sisters. Even to this day I resent that. I think they are more than a half a sister or a half a brother. We loved each other. We have a family organization. All three of the families participate in it. Being the oldest boy, I happen to be the president of the organization. I am just the figurehead really. The others from both families have a very active part. My sister Edith is from Aunt Edith’s family, and she is really a genealogist. She has done a lot of work and helped the whole family in this way. We have an executive vice president from Aunt Irene’s family.

This year in November we have a family reunion. We meet every other year, every odd year in Mesa, Arizona. We come from Detroit. Michigan,. New York. Texas, California and from all over the country. We had children in New York, and they come out. We have a bulletin called Cardon’s Chronicle. This has a message in it which the president gives each year. We keep track of the new members and what they are doing. We have news about the missionaries. We keep track of all their activities this way.

For instance, just recently Lucy, who was one of Aunt Edith’s children and the wife of Brother Lamoreaux over in American Fork, died. We had members from both of the other families who came to her funeral from California and from Arizona.

KJ: It sounds like you are a very close family.

LC: Yes.

Aunt Irene was a good singer, and she loved to sing. I never could sing, but her children could sing. Owen could sing pretty well.

Aunt Irene helped me in many ways. We learned all the introductions in Parley P. Pratt’s Key to Theology. In his introduction for the book, he says, “Oh truth divine. What treasures unrevealed in thine exhaustless fountains are concealed. Words multiplied, how powerless to tell the infinitude with which our bosoms swell.” I learned that when I was fifteen years old, and I never have forgotten it. I could tell you just one more in there. The first chapter is science of theology. It goes. “Eternal science who would fanthom thee must launch his bark upon a shoreless sea. Thy knowledge yet shall overwhelm the earth; thy truth to immortality give birth. Thy dawn shall kindle to eternal day and man. immortal, still shall own thy sway.” This is a great blessing to me because I have lived with this ever since. I do this to show that the interest and the care that Aunt Irene took in me. Aunt Edith did many other things that were of the same nature too.

KJ: You said that your father was a principal and a teacher and your mother was a teacher. Were the other wives also teachers?

LC: Aunt Edith taught.

KJ: Was there a stress on education in your home?

LC: Yes.

There are twenty-nine children in the family. My mother had eight. Aunt Edith had twelve, and Aunt Irene had nine children. This was a large family. There was not one child that didn’t know that my father loved him best and better than anyone else although they knew the same was true of each member. Everyone just knew that our father loved us. He was really an exceptional person I think.

(Tape Interrupted)

KJ: What kind of things do you remember about your father?

LC: He never whipped me but once and that was with a weed. When he disapproved of what I did, it was more of a whipping than you could have had with physical punishment that he would give. I always wanted to have his approbation or approval. I think that this is true of every child.

You know the symbol for peace in China is two women together standing on a street corner. The symbol for war is three women standing together on a street corner. That was not true in my family. I am sure that there were times when they disagreed and had some conflicts. I don’t know, but it never was evidenced in any single time. They showed nothing but love for one another. That was part of what made this like it wasn’t more than one family.

KJ: This was true even though you were in separate houses. You felt at home in each home?

LC: Yes.

When we were at Tucson, we always had separate homes. It was separate tents when we first came out from Mexico. We had tents boarded up part way and a little bit of a floor in them sometimes.

KJ: What kinds of holidays did you celebrate in Mexico?

LC: We celebrated the Twenty-fourth of July and the Fourth of July. It seems like we always went out to the lakes. There were three lakes. the large lake, the little lake and the long lake as we called them. They were about seven miles out from town. My father and Brother Robison, my father’s nephew, got their water from these lakes that they used. The whole community would go out there to bathe and to have picnics. The whole community would be together. Everybody got their surreys out and would travel out there. Sometimes we went down by the river and had picnics down by the river in the other direction.

Christmas was always a holiday. On Christmas I would get an orange, a penny pencil, and sometimes a harmonica. That was good. They kept the Christmas tree hidden until Christmas morning. At night they would get it out of hiding and put all the tinsel on it. They would string popcorn mostly. It would be strung all over with popcorn strings. That, of course, we would get to eat and we enjoyed it. We had popcorn balls.

KJ: Would this tree be in your mother’s home because she was the first wife?

LC: It would be there because we had the biggest home. Aunt Irene and Aunt Edith both had fair sized houses that they lived in. One of them was about a block away, and another one was two blocks away. They were close together. Of course, often they would be at my mother’s house as a group all together. It would be at my mother’s house because it was a large house.

KJ: Would you have meals with just the three separate families?

LC: Yes. we didn’t have them together. My father lived earlier in the so-called United Order which was not really the united order. They had all the men eat first, and the women and the children would eat separately. It was not really the United Order. It served its purpose, and Brigham Young encouraged it even though the United Order was suspended in 1834 just after it had been in just three years.

KJ: It sounds like you had quite a large amount of work to do especially because you were oldest boy. What kinds of things did you do for recreation along with the work you did?

LC: I would hunt rabbits to supply the table. Each morning I would get up just at daylight. Sometimes I would go to the fields in the nighttime with a double barrel shotgun to get rabbits. I would get seven or eight rabbits. That was our meat. I enjoyed this. Lots of time if I could get a day off I enjoyed taking the gun and going out and hunting for rabbits.

It seems like we always worked in the fields except on rainy days. Always on rainy days we fixed fence. That was something we could do in the rain. It seemed like we were busy all the time. Later some of the men folk would have Saturday afternoon off, but we just couldn’t quite make it. I didn’t get to go.

KJ: I understand that your grandmother lived next to you.

LC: My grandmother on my father’s side was French. She certainly was faithful. She had her chickens to take care of and her own strawberry patch. She took care of it herself.

My grandfather was a very austere person. It was a custom not long before that time and even at that time for the wife to call the husband Mr. He had her do that. He always was dressed with a top hat and a cane. He wore the cane for the appearance and not for the need.

There is only once that I remember meeting him face to face. It was on the pathway coming from his daughter’s, Aunt Katie’s, my father’s sister. He lived with her. She didn’t have any children. She had a big house that was practically as big as our house. There were not very many in it. She kept an elderly German bachelor for a gardener. She had two boys that she adopted. That was all they had. He came from there. I saw him coming on the path. There was a gate in a fence between our lots, so I went down the fence to crawl through the fence. He called me up. I think that is about the only time I ever met him face to face. He was kind, I guess. You would have to ask some of the older ones who knew him better.

Grandmother used to pray a loud in French. She would really pray. She had long prayers for several minutes sometimes. I am sure that it was five, ten or fifteen minutes. Of course, we couldn’t understand what she would say. We children would get beside her house. There was just a little breezeway between what she had for a house and where I lived.

After we came to Arizona, our houses that my father had were different for each one of his families. None of them were much of a house. The families would change houses.

KJ: You have mentioned prayer. Was it a custom in your family to have prayer with your whole family together?

LC: Yes, we had prayer morning, noon and night. We prayed every noon. We all knelt at the table at noontime. We would all come in from work and have a meal together.

When I got older, my father loved to talk about the gospel, and I loved to get out of work talking about the gospel. I would get all the questions that I could. What I learned from him really stood me in stead in later years. I think he had more of an understanding of the gospel than most. In fact, in later years I know that people recognized this. So many realized that he understood it. Brother Nash, who was one of the teachers at the Gila Academy and later patriarch in the Arizona Temple, told about how so many would go to my father for counsel. I know that they did. I remember they used to come.

I never went a full year to school after the sixth grade because I had to stay out part of the year to work. My second year I went to high school I went exactly six weeks. That was all the schooling I got that year. When I was in the seventh grade, my mother was teaching in Thatcher, Arizona. She sent me home on Valentine’s Day for a valentine to my father, and that was the length of the year that I had that year. Because of this, I didn’t get much schooling.

There was a Haldman Julius Company that had printed little books of all kinds, physiology, philosophy and all the classics. They were about five inches long and three inches wide. I just wore them out in my pocket. I would take them to the field with me. I had some four hundred of these books. I still have a hundred or two downstairs. I realize now that they are real classics.

Milton’s Paradise Lost and Hiawatha was the diet I was raised on before I was ten years old. I memorized Hiawatha. It always has been easy for me to memorize.

KJ: It sounds like you remember quite a bit. Would you discuss these things while you were working or was this mostly at home?

LC: It was at home. At work we didn’t have time. It would be mostly in the evening time.

In Mexico we had two organs, one upstairs and one downstairs in the parlor. The one upstairs was ordinary size and looked much like a roll top desk. The one in the parlor was much larger and looked much like a modern-day, upright piano in shape and size. The parlor was quite an elaborate affair. Most of the rooms in the house had carpets, but the floor in the parlor was a beautiful quarter-sawed wood and was kept highly polished all the time. There was a regular sized door which led into the parlor from the entrance hall, but the doorway that led into the parlor from the sitting room consisted of two sliding doors that, when opened, would join the two rooms. Those doors matched the floor. When the doors were open a portiere could be drawn. The portiere was made of large glass beads and elongated glass pendants that sparkled with various colors in the light. There was a large chandelier also with pendants that sparkled. My father had a large roll top desk in the parlor. The desk and the organ matched floor. The doors to the parlor were always kept locked with a key so the children could not get in on their own.

When the colonists got ready to come out, the Mexicans were requiring that they submit their guns; they insisted on this. They turned guns in. but they didn’t turn them all in. They would bring their best guns to our house. We had a room, an attic, that was big enough for another floor, to have a three story house with higher ceilings that they made in those days. The only access to the attic was a little door in the hallway. The stairs came up about in the middle of the hall. There were three rooms on this end. Then there was just this small hole that we could crawl up through. The colonists would come with the guns, and my father would boost me up. I would get there, and they would bring me guns. I would lay the guns on the floor up there.

The Mexicans got suspicious. Two or three times the soldiers came in. One time we were just in the act of putting the guns up. The soldiers broke into the house and they didn’t even stop at all; they came right up the stairs and up the hallway. I was going to put the lid down. My father said, “Don’t put it down.” They would see this movement. They came in. and there was a room on that side, a room on this side and a room on the end. I just stood up there over them and saw them there. They came right up under the trap door and one went in all these rooms, but they never looked up.

KJ: I bet you were glad of that.

LG: I didn’t have sense enough to be sorry or afraid. They were intriguing to me. I was excited to see the Mexican soldiers.

KJ: Did you see a lot of soldiers in your community?

LG: Not in our town. We had a field that was on the river in Old Casa Grande. Then there was Casa Grande Nuevo. That was about three miles down by the river. Some of these rebels had taken this little Casa Grande. There were maybe a couple of hundred in there. On this day we saw the soldiers from Casa Grande Nuevo. It was only a few miles apart there. They came with blue suits trimmed with red. red banners and drums beating etc., just like a row of tin soldiers. They kept their order and marched right up to the town. Rebels who were in there deployed themselves out all around generally so they could shoot them from the outside. The soldiers were so disciplined that they would just come marching. They would drop down. We had field glasses. We could see the battle. They did take the place though. They brought the captured out-and just lined them against the wall and shot them.

KJ: You were watching all this. How did you feel about that?

LG: This is what I wonder about, what youngsters feel about it now. It was exciting to me. It was like I played cops and robbers. That was about the extent of it. I didn’t have the feeling of it. Of course, I can’t say exactly. I had just been in the third grade.

(Tape Interrupted)

LC: We had Mexicans working for us. We had a Mexican by the name of Jose at one time.

Mexico had three presidents in about as many months down there at that time. There were several factions. Armies belonging to different factions would come through our area at different times. Most of the generals of such armies would just turn their horses into the fields of the colonists without permission and without pay. But there was on general who did turn his horses into the fields and did give some compensation. This general was Rascon. This Mexican that we had working for us went to war with him. I guess we didn’t have enough work. We didn’t know what to do with him. Anyway at that time we didn’t.

He came back as a follower of Pancho Villa. We asked, “Why did you go from Rascon to Pancho Villa?” “Orosco paga un peso cada dia. Y Pancho Villa paga un peso y dos cada dia.” Orosco paid a dollar a day. Dos realizes is twenty-five cents. Pancho Villa paid a dollar and twenty-five cents, so he joined him. Who wouldn’t for twenty-five cents a day?

Jose had a hat, a sombrero. Everyone prized it, if they could get enough money to get a sombrero. He would have very little money, but he would go hungry if he could get a sombrero. I think maybe his going to war made it so perhaps he had enough money to get it. I really don’t know how he got it, but he was very proud of it.

On one occasion he was on the run. Of course, they were riding on horses. and this hat blew off. Here came the enemy right behind him. He just turned around and went back and got his hat. He was not going to leave that sombrero.

KJ: He was all right; he made it?

LC: Yes.

KJ: He must have been quick.

LC: He just swept it up while riding at a fast pace.

The Authorities finally said we had to leave. They took the women and children out. My father was assigned to go and help get them into EI Paso. Then we went into a vacated lumberyard. Each one of us had a space for one family. It was about the size of what you would park lumber in. It would be about eight by sixteen feet. That wasn’t for the whole three families. At this time the families were broken up for a while. They got separated until we got to Tucson, Arizona. Then we got together.

My father’s nephew had quite a number of really fine horses. We had horses that the foals were worth thousand dollars of money at that time. They were purebred. Some of the brethren were bringing their horses out, and the Mexicans began chasing them. Several of the men dropped back and shot the guns that they had stored in our attic just over their heads. Then they went on. When the Mexicans saw the caliber of guns, they didn’t chase them anymore.

KJ: How did you feel about leaving Mexico?

LC: It was an adventure, of course, for a ten year old as far as I was concerned. It was awful tiring. We went down to the depot, really just a stopping place, and we stayed all night long. The train didn’t come; it didn’t come until late the next afternoon. In fact, we went back to the house. We were just laying there on the ground for most of that period of time waiting for the train. Then when it came, it was just a freight train. It had boxcars.

WC: Your mother said that she was so concerned leaving the home, but she was most concerned with the livestock because she didn’t know what would happen to them. She said that she went out and opened the chicken gate so they could run out and get water. She knew that if she left and it closed up they wouldn’t be able to get it.

KJ: Did they just leave things as they were?

LC: They just had to leave everything. They could take only a very little bedding and the clothes. Each one just had a suitcase for a family I guess. They had a bag or two, but there just couldn’t be many of them. They just packed us in like sardines.

The Mexicans had been getting bolder all the time. They would come and steal the horses from us. One time I was going with my father out to the ranch. We lived in town, but we had this ranch about seven miles out by these lake. As we went by Brother Harris’, they had taken a horse, and they were arguing about it. Brother Harris, whose horse they were taking, couldn’t talk Spanish at all. He couldn’t tell them. My father could speak Spanish. He sent me in to tell Sister Harris. They were related to the Harris that was principal of this school, Franklin S. Harris. My Aunt Edith was related to him.

The Harrises had a boy that was just my age. The mother took this boy and myself up and put us under the feather bed. One of the older sons had a pistol, and he was pointing it out the window. He was a boy although he was much older than we were. He was watching them to see what they would do to his father. He didn’t want to shoot. They finally got it all calmed down.

They would take our horses off the pasture out at the ranch. Then Elmer, my cousin and some of the others would go and find these horses. They would get them back.

The long lake was quite a ways across. It was about one half a mile across. One time I was riding a horse down on one side. We rode horses all the time there. The cattle had come down to drink on the other side of the lake. There were some of the Mexican soldiers on that side of the lake. They just went along and shot the cattle in the water. They slaughtered them just for the fun of shooting them.

My father wasn’t at the ranch house when I got there. So I went to town to let him know. I don’t recall if there was anything that they could do then.

KJ: So there were a number of things like that that happened that would be very upsetting.

LC: Yes, it was getting worse and worse and more dangerous all the time. There was almost anarchy in the nation there. Porfirio Diaz had been a ruler for sixty years I think altogether. He had been a benign ruler; he was good. But he didn’t give any chance for progress. Of course, with their revolution, there was good and bad about it.

KJ: You have mentioned that you just had to leave things as they were. Did anyone ever get to go back?

LC: Yes, they went back. Actually after we left, they went back and that was when they got the horses. They did bring some furniture out also. After many years, in the 1930s, Mexico paid some compensation. At least my father got some money, but it wasn’t anything-like the value of what the things were.

Everybody had a nice place. They built nice big brick houses. They were very beautiful houses if you could see the pictures of them. They are not the style quite that they are here. Most of them were two story with a big attic just like ours. They had plantings around them. They had trees and lawns. Some of the cottonwood trees were still there when I went down there three years ago.

The Mexicans made our place headquarters for the armies because our house was the biggest in town.

George Romney lived down there just across the street from us. Gaskell Romney, George’s father, had a lumberyard. Brother Marion G. Romney who is in the First Presidency lived in Juarez.

KJ: Was your grandmother still with you when you left Mexico?

LC: She came with us all the way. When we gout out here, my father took care of her all the time. Most of the time he took care of my mother’s mother too. Her name was Jane Gibson Sanders.

KJ: That would have been a very frightening time I would think. You mentioned it was sort of an adventure.

LC: It was for me. I am sure that the parents were very worried. I could tell that, of course, especially on several occasions. It was getting really dangerous. The Mexicans didn’t like the gringos. I don’t blame them either because the United States had actually exploited these people down there. The Americans had gone down there and taken everything out. They had left them nothing and paid them nothing. A great deal of this went on for years in all of South America. That is why they have such a hard time getting friends with them yet.

KJ: After you moved to Arizona, were the three families more separate than they had been in Mexico?

LC: No. Aunt Edith’s and Aunt Irene’s families and I lived on the farm. There was a river and a high bench. Where the river had been there was a sandy, loomy area. That was where the farm was. We had silos and things that we had put in for the cattle and for the cows for the dairy that we had. We had two houses. One was not too far from where the milk house and the corrals were so that we could be there to take care of things. The other house was about a block or a block and a half away farther up on the bench.

My mother had a diploma from Arizona State. She taught all around in different places.

KJ: So you and your brothers and sisters stayed with the other two families.

LC: Not my sisters, and I was the only boy in my mother’s family. The sisters were older. My youngest sister was the baby, and she went with my mother. I was the only one that stayed with the other families. The others were going to school or something at the time.

KJ: That was when you got nice pieces of chicken and pudding.

LC: Yes, I got extra sugar on my rice pudding. Sometimes it was farmer’s rice. It actually is flour. I don’t know how they make it so small although it was just flour. It was just a quarter of a inch. That is why they called it rice, I guess.

KJ: Were there other families that had been in Mexico that were living nearby in Arizona?

LC: Yes, this was a community of Mormons mostly from Mexico. There was a man by the name of Bingham who had established the town before the Saints from Mexico came. They called it Binghampton. It is enclosed now in Tucson itself. They have built out to there. There was Fort Lowell, an old fort near where we were in this community but it was about seven miles from town. The town of Tucson has grown and taken that seven miles and far beyond there.

KJ: How did other people like non-Mormons react to your family situation?

LC: There were hardly any non-Mormons there. It was just really a Mormon community at Binghampton. We had a branch there of the mission; we didn’t have a bishop. We were in the California Mission.

Brother Kimball’s brother, Gordon Kimball, lived in about the next house to us. His house was about a half mile away. I used to go up and take organ lessons from his wife. I didn’t care much about the lessons, but I did get out of the work. The work got pretty tiresome there.

KJ: Tell me about how you met your wife.

LC: My mother was teaching in Superior. She was staying at a hotel. My wife’s folk and my wife lived right next door to this hotel. Her mother’s family were the only Mormons in town.

WC: Louis’ uncle, Mine, was my father’s best friend.

LC: He was my mother’s brother. He lived in the town of Superior where my wife lived. When we came out, he sent us a hundred dollars. A hundred dollars then was about like five thousand now. If we ever got a penny or two pennies, that was a lot of money. He helped us out. I guess it was through him that my mother got this school there.

I met my wife then. Her father died just about that time. Her mother was coming up to Salt Lake to do the work in the temple for him. They even did the work for him before a year had passed. That is unusual.

WC: He had expressed a desire to join the Church to the missionaries there. They had it in their records that he had asked to join, so they didn’t hold it to a year. It was more convenient for us to go in the summertime. We went up there. Louis’ mother and Louis went. He drove her car. They went in their own car, and we were in our car. We traveled together.

LC: It took several days to go from Phoenix to Salt Lake. They didn’t have any roads. We were staying in the same hotel up there. I met her and saw her there. I knew that she was the only one for me then. She was young, and I was just starting to school in the university.

LC: I never have thought about anyone else for a wife. I tell my wife this I don’t know how many thousands times. There was never anyone else that I ever considered marrying. I went with some other girls when I went to the Gila Academy. I was popular enough because I played basketball and was a new one in the school. They used to have girls’ choice at dances. When they got up to eighteen ahead, I would tell them that they would just have to take their turn. The first one there would be the first one. But I really didn’t see one that I would have married. I have never seen one since that I would have traded her for.

KJ: When you were in Arizona, did you continue live with your aunts?

LC: It was just the last year or two when I was in the University of Arizona when I didn’t live with them.

The first year of high school we were milking thirty-three cows. Aunt Irene had four boys at that time. Three of them were quite young in those-days, and they didn’t milk many cows so most of the milking was up to her oldest son, who was three years younger than I. We would get up four o’clock in the morning and milk the cows. The other boys weren’t going to high school; I was going to high school. I would ride a bicycle seven miles to the high school. Then in the evening we milked the cows.

The next year I went six weeks. At that time, I got a job at Western Union delivering telegrams and packages. John Carlson a friend and I were the two that started working for them. But in a short time seven or eight other Mormon boys were working for Western Union. Often we would start at four and work until ten at night. Then we would ride horne on our bicyles after that. So we got a good deal of bicycle riding. But it brought in some money. I went to school just exactly six weeks. and then I had to go on the farm and work.

KJ: Did your father continue to trade off evenings with your aunts in Arizona?

LC: With the two, yes. He would stay at Aunt Irene’s and Aunt Edith’s. They did get so there were maybe two or three days depending on the work at sometimes. I don’t remember just how it was arranged, but I know that they changed. I remember definitely that often it was just a rotation around both in Mexico and even after we got out there. My mother would come some times. During certain period of times of the year, she would be there.

KJ: When she carne, would she have a separate place to live?

LC: Yes.

Finally when I lived with my mother, she got a school in Binghamton. There was quite a bit of animosity towards polygamists in Tucson, so she had to stay away from there. Mr. John Mess had gone to school with her, and he knew her. In fact, somebody made some remark about polygamy, and he just up and knocked the guy down. He was a big man. She wasn’t there. It was a remark that they had made. He wouldn’t stand for it all. He got the school district to let her teach there. That was after I started to the university.

I stayed out of school one year. I bought a dairy route. I would pick up the milk and deliver it. I ran it just exactly one year. Then I sold it again. I got the money to start college.

Then I got the first real bus in tne state of Arizona. They hadn’t had any real buses. and I got this bus that was built specifically for bussing people. It was just when they were beginning to bus all the high school children to town. But they had been using passenger cars for buses. I used this real bus until I got married. I drove the bus.

KJ: As your parents got older, what were their reflections about their lives in polygamy?

LC: This is just my impressions. I never really talked with them. One time I did a little, and the answer I got was that it made for better relations among the contracting parties. Now what does that mean? I never really knew. That was the answer I would usually get from some of them.

Right up until the time I left the family, they were all three living in the Chandler and Gilbert neighborhood down near Mesa, Arizona. Finally my father got to have a big broiler factory with thousands of broilers. Always Elmer would be the one to work with my father. He was a good worker, and he would take care of it of actually managing the farm. My father was usually working with other things. He was president of the dairy association of the county that worked to get markets for the produce that we had from the dairy.

In Binghampton we had all three families, but my mother had a house rented right close to the school. When we got married, my mother lived in the Jones’ house before Dan Jones did. That was about the first time that she had come to Tucson.

KJ: How long did she continue to teach?

WC: She taught until she retired. I guess she must have been sixty-five.

KJ: So she really made thata life long career.

WC: She taught when she was having her babies even. She taught really all of her life.

LC: She had three girls in three years and still taught. I think that they were a lot more than teachers. There was more religion in the schools.

When I was bishop in Grand Junction, whenever the General Authorities would come or some of the people would come with them for some special Primary or Relief Society program and they were from Old Mexico. I would say, “I will see if you are from Old Mexico.”

“Abou Ben Adhem (may his tribe increase!)

Awoke one night from a deep dream of peace,

And saw within the moon light in his room,

Making it rich, and like a lily in bloom,

An angel writing in a book of gold;

Exceeding peace had made Ben Adhem bold,

And to the presence in the room he said,

‘What writest thou?’ The vision raised its head,

And with a look made of all sweet accord

Answered, ‘The name of those who love the Lord.’

‘And is mine one?’ said Abou. ‘Nay, not so,’

Replied the angel, Abou spoke more low,

But cheerfully still: and said, ‘I pray thee, then,

Write me as one that loves his fellowmen.’The angel wrote, and vanished, the next night

It came again with a great wakening light,

And showed the names whom love of God had blessed,

And lo, Ben Adhem’s name led all the rest.”

If she couldn’t tell me that, I knew she didn’t come from Mexico. Everybody learned that just at the starting at the fourth grade.

KJ: When you were in the fourth grade and in grade school, would you all meet in the same rooms for school?

LC: No. It was a church house that the school met in. We would have rooms. We had different grades divided in different rooms.

KJ: Which school was your father principal over?

LC: Dublán Town. Of course, he was involved with the general stake. These were church schools and paid by the Church.

KJ: I have the feeling that your experience with polygamy has been that you found it to be something that you remember fondly.

LC: Yes, very much so. I loved everyone, everyone of the children. I saw more of my aunts than I saw of my mother. They treated me with respect and with kindness all of the time.

KJ: You mentioned that one of your aunts had mainly daughters. Would they take care of the laundry and those types of duties for the family?

LC: No, not for the whole family. Each one of them did those things. Aunt Irene had three daughters too. They were younger. They grew and helped take care of things.

The one thing that the wives had in common was the beehives. They had beehives, and they helped care for them. Then we would get Grandma Done who was an expert at it to come. She could almost pet the bees. Everyone else would have the veil on. Sometimes she would wear a veil, and sometimes she wouldn’t. She would go right to the hive. She seemed to know just how to handle the bees. I used to marvel how she could do this.

KJ: You mentioned before that you did things such as raising peas and other things in Arizona to get cash. When you lived in Mexico, did you live off your farm and your ranch?

LC: And off the cattle. My father was pretty well off there. He had quite an estate there of many thousands of dollars. He owned two houses and the lots in town. We had this big tract of pasture land. Then Don Louis Terases was a really good friend of my father.

This Don Louis Terases’ home was a hacienda said to have one thousand rooms. It was built like a fort. He would bring in people or people would come to celebrate an occasion, and he would fill these rooms up. So he was a big man. He did a lot for my father. My father made a lot more in the summertime working for him than he did in the winter teaching school. So he had this source of money that no one else really had.

KJ: After you were married, did you move right to Colorado then?

LC: We were in Arizona after we were married. We have five children, and we were in a different state for each birth. Two of them were born in Arizona, but we were living in Texas for one of them. My wife went to Arizona to have her second child.

KJ: What was your occupation?

LC: I went with a law correspondence school shortly after we were married. This came right at 1929 or a little before. We were beginning to feel the pinch of the Depression, so I didn’t finish it.

I lived in Texas for four years. I was the president of the first branch of the town of San Angelo, Texas.

WC: Then we were transferred to Albuquerque and then to North Dakota. We went to Albuquerque because we had been through it and liked the idea.

LC: We liked Albuquerque. I took the examination for the post office just about that time.

I went out and worked on the chain gang for a while in the Oklahoma Oil Company. It was just like being in the prison. All the escaped prisoners were in here. Officers would come frequently in the night time. We slept in long tents. We did anything then to get something to eat. We had the Depression right after that. I think there were fifty in a tent with twenty-five cots laid just as close as you could to get them with no room between them. Many a night at four o’clock in the morning the guards would come in and pick up this guy and that guy for prisons. They had escaped from prison. It was pretty wild.

They had just discovered oil down there. They were competing with some other Texas company to get an oil line finished to McGammy, Texas. There were brawls and fights all the time.

We would get out at four o’clock in the morning, and there would be a pot of spaghetti. That was what our breakfast was. It was spaghetti and catsup. Catsup was the sauce.

Then we would get on an open truck. We would drive for about an hour from camp to get to where it was. It was hardly ever that we were going along that they didn’t have to shove two or three off and let them finish their fight. If anybody started it, they would just make them get off, and we would go on. This was in about 1929.

KJ: What do you remember of the Depression?

LC: I was lucky to get the top grade in the post office. Out of the top three they could choose one to make sure they knew who they got. That was pretty secure. At the post office, we had a job although we only got Sixty-five dollars a month. But that was good.

I remember wages going down to two or three dollars for a day’s labor. I went down to Mesa, Arizona one time for a vacation. While I was there, they were picking cantaloupes and packing them. I got a job on a machine sorting them and then packing them on the machine. I got eight cents a crate, and I did a hundred crates. I got eight dollars, and that was big money. I was really happy. The first night the guy came and fired me. He said, “You are too slow.” My brother had worked there, and he had put in three hundred crates. He had been doing this for some time, and that was the first time that I did it.

They had them hauling on little flat wagons to bring the melons in. For that they would have two men and a driver. They would load from both sides. I said, “I will tell you what I’ll do. I’ll load up and bring just as many loads in by myself. You just have the driver and let me load. You pay me time and a half what you pay the loaders.” That went a couple of days, and he came and said, “I can’t do this anymore.” I said, “Why? You owe me that. You are keeping up with them.” He said, “They are all complaining about the money that you’re getting.” I would get time and a half for what I counted. So I got fired for being too slow and too poor and then fired for being too good.

During the Depression, I was working in the post office at Albuquerque. At that time the rural routes were kind of gems that the retired congressmen would want because they paid lots more. They wouldn’t go work in the post office. but they would get this route and get someone to run it for them. There was a route up in North Dakota that was available. It was pretty long. It was a fifty-two mile route. That would make $2700. That was a thousand dollars more than I was making at Albuquerque. Actually, it was more than double. That was the reason we went up to North Dakota.

I contracted hay fever up there. After about five years I had to get out. That was when we went to Canyon City, Colorado. We had a child there. We had one in North Dakota, Colorado, Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico.

KJ: You mentioned that you had just recently taken a trip back to Mexico. What kinds of memories did it bring back?

LC: This brought a lot of memories. It seems like it just burned in my memory. I went to different places. I went to Diaz. I know how old I was when I went up there; I know how old I was when I lived in Juarez when my mother taught up there. I can pretty well establish the things that happened there.

There were a lot of little things that happened that were big to me. In the wintertime my mother would go up to Diaz to teach, or some other colony.

In the summertime she would come to Dublán. During the summer she had an ice cream parlor. That was in one of the houses. My mother would just come in the summer, and she was living in this house that my aunt had been living in. Aunt Irene would live in the big house. We had a big strawberry patch, and my mother would put real strawberries in homemade ice cream. Anyone but her children would get it. If I got to lick the paddle, that was good. They would come there and get it for a nickel or a dime. She sold it on plates. It was delicious when you would get it.

The ice came from EI Paso, Texas. It came on a flat freight car out in the sun. It would be three hundred pounds when it left EI Paso, and if we got fifty pounds, it was pretty good.

KJ: Would she chop it up herself?

LC: No, she had her son chop it up and turn the freezer.

KJ: Was that you?

LC: Well, she only had one son. I didn’t do all of the chopping and churning I guess. but I thought I did. It seemed like a lot.

KJ: That must have been a popular place there.

LC: It was. Everybody knew about her. They would come from far and wide to get the strawberry ice cream. They had vanilla too.

One time there came a hail. It hailed so much that they stored the hail away in the granary that we had there. That lasted all summer long. They put gunny sacks over it and piled straw up over it. That was really a good year. That was for the ice for the ice cream.

I remember the granary was bigger than this room where we put the wheat. Everyone raised their own wheat or else they would swap peaches for wheat or whatever.

Of course, we paid the tithing with wheat. I would hear my father tell about where it says in the third chapter in the last book of the Old Testament, “Will a man rob God? Yet ye have robbed me. But ye say, ‘Where in have we robbed thee?’ ‘In tithes and offerings. Ye are cursed with a curse for ye have robbed me, even this whole nation. Bring ye all the tithes into the storehouse that there may be meat in mine house,’ saith the Lord of Host, ‘and prove me now herewith if I will not open you the windows of heaven and pour you out a blessing that there shall not be room enough to receive it.'” I knew my father paid tithing, but I never did see that wheat get so full that it wouldn’t hold it. That used to worry me. I was concerned because he paid his tithing, and then there was not going to be room enough. I didn’t see the wheat grow tall. That was what I expected it should do.

Maybe Bowmans had water in their house. We were about the only ones that had water in the house. We had a well, and some of them had barrels. We had a big tank. When they made the big house, they made a bathroom upstairs and a bathroom downstairs. The way we got the energy to get this water in the house was with a pump that we had a horse on. The horse would pull it, and it would go round and round. This was my chore to ride that horse around. Old Kit was a horse that weighed a ton and stood eighteen hands high. I couldn’t reach up even to the hame. I had to catch a hold of the tug and get a ways up. The problem with that was that Kit was just as nice and tame and lazy as could be. That was why I had to keep riding her all the time to keep her going.

She would stomp. The flies would get on her legs. I never wore shoes down there. It seemed like I had my toes smashed all the time. She would just stomp on my toes until I really never got a well toe.

KJ: Would you have a schedule for baths?

LC: I don’t remember exactly. The bathrooms were not in all in the house. They had their outhouses and in the other places they had big barrels full of water, so they didn’t have to go out to the well all the time for it. We had this one house, and there were not that many of us in it at the time. Isabelle, my younger sister was born down there, in Mexico, but she was just a baby. She was seven years younger than I was.

KJ: How would they take care of the laundry?

LC: They rubbed the clothes on a wash board.

WC: About taking a bath, my grandfather used to carry three one hundred dollar bills in a little tobacco sack. He would sew it inside his fresh underwear every time he took a bath. He kept it there just as an emergency fund in case he needed it.

KJ: You mentioned you had this water tank on your home. Where did the water come from?

LC: From a well. This horse would go around and it would pump the water up into the tank. It was a lot of water. We were glad to have the water then. I liked it better there than when I would go to Aunt Irene’s or Aunt Edith’s because at their houses they just had barrels.

We used to have three ollas. They were made of a porous clay, and they had them all different sizes. The ollas that we had stood about two feet high. Then they would flare up at the top. The evaporation through that clay would keep that water cold. We had a dipper with a long handle, and we could just get a drink of cool water. In summertime often people” would drop in to get a drink of cool water.

WC: Sometimes they were wrapped in burlap.

KJ: As people went down to Mexico, were there things that they learned from the people there?

LC: There weren’t many Mexican people in Dublán. In the town of Casa Grande Nuevo, there was a store and a shoe shop. As I said, we hardly ever wore shoes.

One time I got a new pair of shoes, and I thought it would be real fun to have shoes on. I walked up about three miles and got these shoes. I put them on and walked back. When I got back my feet were so sore that I never wanted shoes again.

We didn’t like to wear shoes. The girls, of course, wore shoes. Girls had to wear shoes.

I remember my mother scolding the girls about going out without their bonnets. The bonnet would cover down the sides of their face so that they wouldn’t get to looking like Mexicans.

KJ: What were your Sunday meetings like in Mexico?

LC: They had sacrament meeting in the afternoon. I think we had fast meeting on Thursday. I really don’t remember anything about Sunday School there. I dreaded going to meeting because nobody knew when they were going to be called on. Even the children were called on to speak. I would just hide down behind the bench there. I wasn’t ten years old. I was frightened half to death. One time they told me to prepare “faith is the evidence of things not seen; the substance of things hoped for.” I memorized that, and I said that.

KJ: Did you ever get called on?

LC: Yes, I got called on one time just to come up and bear my testimony. I didn’t have that much of a testimony. I just knew that my father and mother said that it was right. That was a testimony, of course.

KJ: The church was the same building that the school was held in.

LC: It was really a church house. They had a big hall where they would hold dances. They danced a lot. It was quadrilles mostly. We did get to two steps. The whole family would go; everybody would go to the dances.

That was the same in Tucson. Everybody would go to the dance. We had a dance once a week every Friday night. We called my cousin’s wife Aunt Retty. She was a Call. Anson Call was quite a figure in the Church. She was quite heavy; she was fat. But she made the best candy, all kinds of candy. I would take it to the dance and sell it at night for her and get a commission on it. Of course, I nearly always ate more than my commission. She was really patient with me.

She was really a patient person. When I was fifteen years old, my father told me that I could grow some watermelons and I could have whatever I made off of them in a certain area. She and Roy, my cousin had chickens. They lived half a block from us. She had a chicken fence, but the chickens always were out. I told her several times that they were just ruining my watermelons. They were just blooming, and the chickens would come up and pick holes in the small melons.

So one morning I went out. There their chickens were in the melon patch pretty thick. I had a double barrel ten gauge shotgun. I just fired into the chickens. I killed about four or five chickens in the one shot. Then I went over and told Aunt Retty what I had done. I expected to get fits for it. I took her chickens over to her place. You know what she said? She said, “Well, we will just have a good big chicken and dumpling dinner.” She cooked those dinners, and our family and her family came. Did we ever have chicken and dumplings! That was a treat.

KJ: Do you remember the kinds of foods that you would eat in Mexico and in Arizona?

LC: I don’t really remember that in Mexico. We had big gardens. We had sweet potatoes, potatoes. strawberries and peas and radishes and all the vegetables.

They made the lots down there in Mexico ten acres like they are in Salt Lake. But there would usually be just two families on the lot. We had five acres. This was separate from the farm land. We would have a garden on the lot. We had water running down each street. The ditches were on both sides, and they always had water in them in the summertime. I guess they turned it out in the winter.

They always had water, and people had plenty of water to make their gardens. So everybody had gardens.

We put up things; they would can them. They made their own soap.

KJ: There would be enough supplies like the bottles there or would they have to go to El Paso?

LC: There was a union mercantile, a general store. Off her strawberry patch and her chicken, my grandmother had a sizable sum in this union. She had two or three thousand dollars. That was a lot of money in this union mercantile. My Aunt Katy had a lot invested in it. I don’t think my father had any. He invested his money in this cattle ranch; he had a lot of cattle. They sold things from the grocery.

KJ: That kept you supplied pretty well with the things that you could not take care of on your own then.

LC: Yes.

One time I went to the store. My father told me to get some ten penny nails, twenty cents worth of ten penny nails. I went to the store, and I said that I just wanted ten penny nails. They said, “Well, I think your father wants this.” I insisted that I just wanted ten nails. I got ten nails. There was a lot of money left over. They said, “What are you going to do with this? I said, “I will get piloncille. Piloncille was a kind of a candy that was hard. If you chewed on it, it would get softer so that you could get a bite off of it. It was about two inches in diameter and about four or five inches long. That was the shape of them most of the time. I had enough to get me one of those. When I got home, I hadn’t done right. My papa didn’t know what to make of it.

I can’t remember even now why he whipped me the one time. There were weeds that grew in the neighborhood sometimes, and they were hollow. We improvised; we would make bows. Then we would put a nail in this end of this weed. It was straight; it was like a reed but it was hollow inside. It was very light, but with that nail in the end of it we could shoot a long ways. That was the kind of a cane he used to whip me with that one time.

KJ: In situations like that, he would just talk with you.

LC: He always told me. He would show me the wrong and why it was wrong.

KJ: Would he be the one to discipline the children or would your mother and your aunts be the ones to do that most often?

LC: My mother and aunts would. I don’t like to tell you this. We had what we called dark closets. Upstairs in this room where I told you Brother Tanner and I slept there was a closet that had a lock on the door that went into it. It was a sizable closet. None of the children would dare to go in there; it was too dark. Here was where they would put the Christmas toys and the Christmas tree. We had a big, wide stairway that came in and that went up and turned part way up and then went up the other way. The room where you came in from outside was a big room or hall just like you see on some of the old houses. That was the style they had. Under the stairway there was a closet, and it was dark. This was where my mother put me when she wanted to discipline me. I was scared to death of the dark.

My mother would send me out for a switch. I knew enough not to get too small of a switch because then she would get a great big one. It was always a problem for me to determine what size switch I should get. If she thought it was big enough, then it was all right. I wanted to get as small as she would accept. I had experienced it a time or two when I brought in a twig that was too small, it didn’t work.

In Juarez the McClellens had an orchard. We lived in a house in the orchard. They lived in the main house, and we had the other house they lived in before they built a new big one. My mother taught one year and rented the house from the McClellens. It was right along side of a hill. We had a cow named Pinky. Katie, my sister, was five years older than I, and she milked the cow. I was just getting so I could milk. I always wanted to milk. I wanted to find out how I could get more milk than Katie did.

We had two bridges. There was a bridge built high and went over the ditch of running water. Then there was another low bridge that was just over the water. It was a narrow bridge that went across the water. The other bridge was so high that you could walk up and walk across it. It had arms on the sides. I came on the run one night with a bucketful of milk. Mother couldn’t believe that I had that much milk. I had overdone it. I had dipped it in and got water out of the ditch. It wouldn’t work. They finally let me have the privilege of milking all the time.

LC: I don’t know whether they threw it all out or not. It was dark, and I just couldn’t see how much I got in. That water was coming. fast, and there was quite a bi t of water.

For recreation I always liked to hunt, even down there. I had a .22 gun. My uncle who lived in Diaz had given us two presents. He gave a big blunder bust gun. Those old .44 blunder bust guns were big guns. It was a long thing, and you loaded it with powder, etc. He gave us a horse also. We called the horse Gold Dust. It was gold in color. It was for Katie and me to decide which we wanted to have. We drew. She got the horse, and I got the blunder bust.

Aunt Katie’s adopted son was the age that he wore a handkerchief in the back pocket. That was the style then.

KJ: Was it a red handkerchief?

LC: It was not always red, but it was generally red. The part of it hanging down might be blue or it might be white. But he was to have half of it hanging out. He played ball; he was on the ball team. He inveighled me in to trading this blunder bust for a .22 that he had.

I took the .22 out to the ranch. There was a roadrunner sitting on the fence. You are not supposed to shoot roadrunners, but they didn’t tell me that at that time. That was something to shoot at. I would shoot at rabbits, squirrels, and things. I shot at the roadrunner, and it just sat there. I would come up closer by a mesquite tree. I got as far as from to the corner of the house, which was about ten feet, and shot a whole box of bullets. I never even scared it. What had happened was that gun was leaded, not ever a bullet came out of it. All of those bullets were in it. My father really got after this boy for giving it to me that way. I didn’t know it.

I could have had that thing explode right in the face. I don’t know why I didn’t get the blunder bust back again. I wish I had; it would be worth a fortune now.

I think it is just as hard on the man as it is on the women to live in polygamy. My father was even handed with everybody, every member in the family I think. I never had any sense of any problem because of the three families. I never ever thought of that way. It was just one family as far as children were concerned.

The older girls may have thought differently because they lived for three or four years before the marriages. Katie is five or six years older than I am. Aunt Edith had a baby, and my mother had twins, a boy and a girl that didn’t live but a short time. They died the day that they were born. My Aunt Edith had a baby and they named it Louie. It couldn’t be named after me, but she often mentioned this. I was just the same age as the baby she had, she was taking care of both of us when I was a baby. We were “twins.” She considered that she had twins.

KJ: Do you recall the medical services that you had in Mexico? Would they have midwives come in and assist with the births?

LC: There were always midwives. Aunt Edith’s mother was a midwife. Even after we got out to Arizona, she would do this.

KJ: Would midwives also help in other areas beside child birth?

LC: Yes. Aunt Edith’s mother was just a wonderful worker. She was busy all the time. Everyone respected and loved Grandma Done because she was that way. Everyone knew her as Grandmother Done.

Even after she died there was another family of Dones. They were Abeggs. She was the other wife of Brother Done, and she took over after Grandmother Done. She was just like her.

KJ: When you got sick, what would happen in your family?

LC: My father’s brother, Joseph Cardon, lived across the street. Joseph Cardon was a very spiritual person, and he worked in the Church a great deal. I think he was only about fifteen or sixteen years old when he went on a mission. He was very young. He filled a successful, worthy mission. He got typhoid. He had two families in one house. It was a smaller house. While he was sick, they brought him over, and he used our parlor for a bedroom. He died at that time.

There was a siege of typhoid. I had it; my sister Katie had it. Practically all the family had this typhoid. There was a Gentile doctor that lived in the Casa Grande. There were some non-Mormons who lived in Casa Grande Nuevo. He would come down from there to doctor. The main medicine any time they suspected you were getting sick was castor oil. I drank bottles of castor oil I think.

One Sunday when I was recovering from typhoid fever, we had chicken. We had what we called a dumb waiter. We had the kitchen and then a pantry. It was a large pantry, and they had a good deal of things stored in it. Then there were four cupboards that opened from the pantry through the wall to the dining room so they could just pass the things through to the dining room. There were shelves that they put things on. They could open the cupboard doors in the dining room and take the things off those shelves. Everyone had gone to Sunday School except me, and I was getting better and was pretty well. I was up and around. We were going to have a chicken dinner. I was home alone and found this chicken on this dumb waiter.

Then I was dumber than the waiter was. I ate chicken and just ate a lot of it. That pretty nearly was the end of me. I had not had any solids to eat for weeks. I had been sick for weeks. It tasted so good that I thought just one more won’t hurt.

For colds they blew sulfur down our throats. They just roll a paper up with one end bigger than the other. It was big enough just to put into the mouth. Then with a sudden blow they would blow all that sulfur that they had in the paper down the throat. It was just like choking us. That sulfur would come down and just fill our throats and choke us. We had to swallow some of it. It must have made me feel better. I know that I lived anyway. I wasn’t sure when they did that, that I would live.

We entertained too. I was always the center of attraction when my folks had parties, or at least I thought so. When they would have parties, they would open up the sitting room and the parlor. They would draw back the curtains. They were beautiful beaded petitions. We had a big organ that was made like a piano. We used this organ in the parlor. They were always singing songs. The finale of the party was a hobby horse. I would be the hobby horse. I would put my hands and feet in the sleeves of a shirt. Then they would stuff the shirt with pillows. It made out a horse. This would be the show of the evening I thought.

I am sure I annoyed a lot of them waiting to get to it. But I am sure they all wanted my part of the show to come because it always got a laugh. They had to, of course. (laughter)

My father was choir leader too. He could sing well and so could Aunt Irene. So they had some children that could sing. Parley, my brother, was three years younger than I. He was Aunt Irene’s eldest child. He went to the University of Arizona after I married and left. He became the manager of the glee club. He sang in it. They took this Arizona glee club to Hawaii and all over the country. At that time it was unusual. Now, of course, everybody goes everywhere. This was fifty years ago.

KJ: Would you have singing in your home with the organs?

LC: Nearly always.

We would have little games like guessing numbers from one to ten. I can’t even remember now how I did it, but it seemed like I had awful good luck in this. We played different games. We played games that children played.

I always think of a second cousin, of mine when I am reminded of children’s games. He was the son of this nephew that worked with my father. His name was Joseph.

He lived out on the ranch. He had a cart and a horse named Dolly that was a really lively horse. When he would come to town with that cart, all the children wanted a turn to ride on it. Everybody liked Joseph. I never saw this young fellow lose his temper. He was pleasant always; he never quarreled. When we would sing our Primary song, “Jesus Once was a Little Child,” we would sing the line “He played the games that children played, the pleasant games of yore. But he never got vexed if the game went wrong and he always spoke the truth. So little children, let you and I try to be like him, try, try, try.” I get to thinking about Joseph when I hear that song. He just personified it all his life. I knew him later in life and he was still the same.

It seems to me that in considering the matter of the principle of plural, polygamous marriage, one should always bear in mind the purpose and the reason for such a marriage and how it must be practiced if it is to be successful. We know that righteous men in ancient past, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Moses, David, and Solomon had plural wives and that the Lord justified them except in cases of abuse. But the Lord forbade the Nephites to have more than “one wife and concubines he shall have none.” One reason being that both the Nephites and the Lamanites were children of Israel, thus they were the Lord’s “people” and “heritage,” and they were isolated from all other peoples. However, the Lord also declared to the Nephites that if He wanted to raise up a holy seed unto Himself, He would command His people. The Lord needed to have His newly established Kingdom built up and strengthened so He commanded Joseph Smith, through revelation, to institute the practice of plural marriage, under very strict rules. It can only be practiced under the Divine Patriarchal Order of Marriage which makes fathers and mothers spiritual as well as physical parents. Joseph Smith stated that the practice of plural marriage was “a commandment of God for holy purposes.” To be successful it must be practiced on a high spiritual, moral, and idealistic plane. This places grave and great responsibilities upon the fathers especially and the mothers in such families.

I feel that our father met those great responsibilities and test (a test that Joseph Smith stated “was the greatest test of faith”) because his whole household, loved, revered, and respected and obeyed him. I also feel that all three mothers fulfilled their obligations and responsibilities because all twenty-nine children grew up loving one another and with a love for the Lord and the gospel.

KJ: Thank you very much.