by Edith Cardon Thatcher

a Granddaughter

The ancestors of Louis Philip Cardon and Susette Staley have been traced back several generations in the Piedmont Valleys of Italy to 1644. Some of the maternal lines have been traced to the middle of the 1500s. Connections have not been made out of the valleys, but they were of French extraction, since French was the main language, they spoke.

These people were known from the twelfth century as Vaudois, Waldense, or Walloon and were driven to various parts of France, Switzerland, and Germany, then to the final refuge in the High Alpine Valleys of the Piedmont. They sent preachers out, first openly, then as opposition grew, disguised as tinkers and various other occupations, gaining many adherents. They were constantly pursued as heretics and had two Crusades directed against them. They were subject to unjust taxation, many persecutions, and as late as 1848 the law forbade them entrance to any of the universities or the professions. However, they owned their own homes and in 1848 were permitted to enjoy civil and political rights but were still restricted in their religious worship. This background-built character, and they were ready to accept the Gospel as preached by the missionaries of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when they finally heard it.

Philippe Cardon had accumulated enough money by 1836 to purchase a large vineyard and an orchard in the valleys of the Piedmont, and there he built a good, comfortable home. Unfortunately, this was shortly destroyed by fire. His eldest child was seriously ill upstairs at the time, and they felt fortunate in being able to save her. It was the middle of the winter, so there was even more hardship. However, they were able to rebuild, and by the time the Mormon Elders came were in good circumstances.

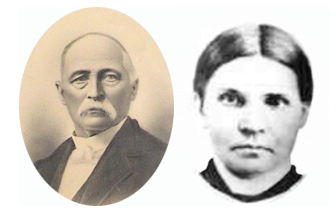

Louis Philip Cardon was the fifth child of Philippe Cardon and Marthe Marie Tourn. He was born March 9, 1832, in Prarustin (Prarostino), Torino, Italy. The other children were Anne, Jean, Barthelemy, Catherine, Marie Madelaine, Louise, Jean Paul, and Thomas Barthelemy.

Louis Philip’s young sister tells in her autobiography of a dream she had as a very young child. Three men came to her and told her they were the servants of God. They related the story of the restoration of the Gospel, about the Prophet Joseph Smith and his vision, along with many other truths. Continuing, they said the day was not far off when her parents would embrace the Gospel. Many things concerning their departure from their home and the long tedious journey they would take as they went to Zion were also mentioned. When she awoke, she felt so strange that her mother wondered what had happened. When the father came in, she told him how strange the child was acting. He listened to her as she told him the whole story. The mother also listened and stored up every word she heard. Relieved, the child then forgot all about it, as a young child would.

The father, Philippe Cardon, was an architect and was directing the building of a large house one day about 1851 when a man came from La Tour, quite a distance from his home. This man said some strangers were teaching and preaching some very strange doctrine and related what he had heard. Philippe listened intently and knew then that these men were teaching and preaching the very things his young daughter related to him as a child from the three strangers in her dream. He immediately put down his tools, saying he would go find the strangers.

He walked all Saturday afternoon, all night and the next morning over the mountains and down the valley. He reached the Palais de La Tour in time to find these men and hear them preach. After the meeting he went to them and invited them to come to his home and make it their headquarters.

At the October Conference in Salt Lake City in 1849, many missionaries had been called to go preach the Gospel to the nations. President Lorenzo Snow, Elders T. B. Stenhouse and Joseph Toronto were sent to Italy. After checking around, President Snow felt impressed to go to the Piedmont Valleys. When they got there, there were about 22,000 Protestants and 5,000 Catholics. They had been but a short time at the Palais de la Tour and were laboring hard. While they were allowed to preach in the streets it was hard to get contacts, so they were glad to accept the invitation to the Cardon home.

Marie Madelaine was now about eighteen years of age. She was reading a book and did not see them approaching. When she heard her father say, “This is my daughter who had the vision I told you about,” she looked up quickly, and recognized them and the dream came back to her memory.

Philippe, his wife, their son Louis Philip and his brothers were soon converted to the Gospel of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and were baptized. The sisters were slower, studying more but all joined except one whose husband forbade her to even listen to her sister. Their minister tried to stop the conversions but could not.

The congregation grew to about fifty faithful members. Meetings were generally held in the Cardon home, but as the crowds came from far and near, a bowery was built, and meetings were held there. The Cardon family often served food to those who came so far. Opposition became strong and, on occasion, mobs threatened them.

When Philippe Cardon received word to prepare to go to Zion, he decided in February 1854 to sell his home. Since he was in a hurry, he did not get full value, but enough was raised to leave. A few days before they started the Elders held a meeting, giving instructions for the journey over the great ocean and the desert places and gave them a blessing saying if hey obeyed the principles of the Gospel faithfully they would reach their destination safely and in good health in spite of the dangers.

Three days before they left, friends came to bid them goodbye knowing full well they would never return. Eight of the Cardon family left for Zion. They had with them a family of five who had no money of their own. They could neither understand nor speak English but soon met Elders who spoke French as the Cardons did, so gradually they picked up the language.

First, they went to London where two weeks were spent making the necessary preparations. Then they went to Liverpool where they waited seventeen days for their ship to be completed. There were 485 passengers, all Latter-day Saints, except the crew and captain.

The first few days out were good sailing. Then a terrible storm arose. The ship rocked to and fro and finally the captain ordered the anchor to be dropped as they were about onto “the Rock of Providence” as he called it. The captain said no ship ever hit that and had survivors. However, calm weather finally came, and drawing up anchor, they sailed on. On reaching New Orleans, they were transferred from the sailing ship to a big steamer.

Some of the company who went ashore to view the City of New Orleans contracted cholera. In a short time, cholera broke out on ship, and they were quarantined on an island not far from St. Louis. Quite a number died.

The father, Philippe, contracted the disease. For a time, it seemed that death would come. But through faith and prayer he recovered. When the cholera abated, the family and Saints continued their journey up the Mississippi and camped above Kansas City. Here they began final preparations for the journey across the plains. However, cholera struck again, worse than before. Many died, sometimes as many as fifteen or twenty a day were buried. This too finally passed.

The Cardons left with a few others as soon as the oxen, cattle and covered wagons could be readied. Louis Philip and his two brothers had a wagon with three to four yokes of cattle each. The roads were rough and there were many steep dug ways, so they often had to stop for repairs. At times they were frightened by Indians, but the captain of the company was crossing the plains for the third time, so he knew how to deal with emergencies as they came up. They finally arrived safely in Utah.

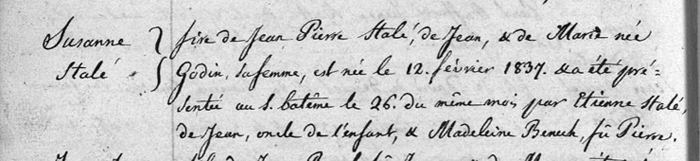

Susette (Susanne Stalé) Staley was born February 12, 1837, in Angrogna, Torino, Italy, in the Piedmont Valleys, and was the daughter of Jean Pierre Staley and Jeanne Marie Gaudin. Her parents, being thrifty became quite prosperous, having two homes, one in the mountains and one in the Valley at Prarustin. They spent summers on the mountain with their sheep and cattle, the winters down where it was warmer. They lived mostly on their own produce.

Susette had a long way to go to church. She was religious and learned her catechism so well she was always able to quote long passages from the Bible. When the missionaries came, she went wherever she could to hear the Gospel preached. Opposition arose as the Church grew, with mobs trying to break up the meetings. On one occasion in 1855, Elder Franklin D. Richards and two other missionaries were forced to hide in the high mountain passes from the mob, going without food for three days before being found by the Staley family.

Elder Franklin D. Richards was instrumental in getting members of the family to emigrate. They were in the company overseen by Elder Canute Peterson and sailed from Liverpool, December 12, 1855, on the Ship John J. Boyd. There were a number of other families from Italy and some 500 saints from Scandinavia and Great Britain. Immediately after their departure, the Italian Mission was closed and was not reopened again for forty years.

They arrived in New York on February 15, 1856, and went from there to Florence, Nebraska by rail, stopping at Chicago and St. Louis on the way. They were delayed for three months waiting for the handcarts to be completed, then joined the first handcart company which left on June 9, 1856, with 273 in the company. Many things have been written of the trials and tribulations, acts of faith and heroism of those who came in the handcart companies.

The father, Jean Pierre Staley was not well when he left Winter Quarters and became progressively worse. It is said that he did not eat all the food issued for him, saving it for his children. Susette and her brother Daniel did most of the work after he became ill. He told his wife he would never reach the valley, but that she and her children would, and that they would never want for the necessities of life. The second morning that he had to be helped into a wagon, he died. His body was wrapped in a sheet placed between layers of sagebrush, and was buried on the banks of the Platte River, opposite Ash Grove. His death was entered in the diary of the handcart company, August 17, 1856. A bonfire was built over the grave to keep the Indians and coyotes from finding it.

The company arrived in Salt Lake Valley on September 26, 1856, and was met at Willow Springs by President Brigham Young and many others. The Cardons from Ogden met the widow and her younger children and helped them to get settled in a dugout. Susette and her sister Mary went to work to help the family. The trials and tribulations made her faith grow stronger and dearer. The twenty-fourth of July was sacred to her and took precedence over all other celebrations.

Louis Philip first married Sarah Ann Wellborn. No children were born to this union. In 1857 at Logan, Susette and Louis Philip Cardon were married. Their first two children, Joseph Samuel and Emanuel Philip, were born in Ogden. The daughter, Mary Katherine, was born in Logan. They next moved to Oxford, Oneida (now Franklin) County, Idaho where Louis Paul Cardon and Isabelle Susette, who died when about two years of age, were born. They persecution because of plural marriage became so persistent that Louis Philip traveled to Salt Lake City to ask advice from President Brigham Young. President Young arose from his chair, smote the palm of one had with the fist of the other, and said ”Brother Cardon, it is about time for the Saints to move to Arizona, as I have been thinking about. Be here in a week with your wife and belongings. The Company will be ready to leave”.

Again, there was a long journey. They settled first at George Lake’s Camp on the Little Colorado in Northern Arizona. The camp was later called Obed. In February 1877, he and his family moved to Tenney’s Camp. Here they lived in the United Order, being on the first roll taken. This called for sacrifice as the Cardons had ample supplies for two years. They were active in church and building up the community.

After two years they moved from Woodruff to Taylor. The Woodruff Ward was organized on September 26, 1879, when the name was changed to Tenney’s Camp. They had hoped to make Taylor their permanent home, but peace was not possible for those practicing plural marriage. In 1885 President Taylor advised Louis Philip, his first wife Sarah and his son Joseph, to move to Mexico. Emanuel and Louis Philip went along to help the families move, but Louis Paul returned to Taylor where he had married and stayed there with his mother, Susette, until 1896 when he was called to go to Colonia Dublán to help with the church school. Susette and her daughter Mary Katherine Cardon Clawson, wife to Joseph I. Clawson, accompanied him and his family. The father, Louis Philip, had settled in Colonia Juarez, where he stayed until a couple of years before his death.

The town of Dublán was blocked out in the Mormon way: A mile square, divided into blocks of ten acres each, minus a large street all the way around. Louis Paul and his sister Katie were able to purchase a block across the street from their brother Joseph, so once more the brothers and sister were together. They were active in church, community and civic affairs, in addition to teaching and supporting the schools. Louis Paul led the choir too.

The farms of the colonists were in town. Irrigation was a problem, so it was decided to build what was called “The Big Canal.” Louis Paul did all the surveying, and his brother Joseph was the chief engineer. The men of the community worked hard to get the project completed. When the new irrigation system was laid many shook their heads saying, “he can’t make water run uphill.” Both Louis Paul and Joseph contracted typhoid fever before the project was finished, and Joseph died. Later, the whole town turned out for a parade and dedication service when the canal was finished. Susette said she felt as though she was going to her son Joseph’s funeral, as to her, the work seemed like a monument to him. The water was turned into the canals, and they worked perfectly. Plentiful water made the farms produce more and prospects for the colonist and their future were more encouraging.

The industrious and thrifty habits of Susette kept her family well clothed and well fed. She wove her own cloth from wool, coloring it with plants and indigo. She even made suits for her husband and sons. These clothes were durable and beautiful, and some were good thirty-five and fifty years later. She lived to be eighty-six years old and many of her grandchildren remembered her dresses. They were old-fashioned then but on her they looked very beautiful.

She always preserved meats, vegetables, and fruits. But her specialty was strawberries and cream. She planted strawberries both in Arizona and Mexico. Her Strawberry Parlor was a popular place to gather. She was successful in drying strawberries and after her move back to Arizona, the University of Arizona Economics Department asked for samples of the, saying they had never heard of strawberries keeping in places like Arizona and Mexico. She was very generous, and many a friend received strawberries from her.

Louis Philip Cardon died of typhoid fever and was buried in Dublán on April 9, 1911.

Dublán Memorial Cemetery, Colonia Dublán, Chihuahua, Mexico

Susette continued to live near her son, Louis Paul, as she had done since the days in Taylor. Her testimony of the Gospel never wavered, and she always did whatever she was asked by those in authority.

When the Saints were driven from Mexico during the Madero Revolution, she had over six thousand dollars in stocks in the Union Mercantile store. One of the greatest trials of her life must have been to be reduced from a condition of easy independence. She never complained or mentioned what she had left behind as so many of us did.

When the colonists finally knew, they were going to have to leave Mexico and would not be able to take their treasured possessions, many tried in various ways to hide them so they would not be stolen. Some dug holes and buried things that would not rust. Susette was asked by someone if she wasn’t going to try and do something of the kind. She replied, “No, they will never touch any of my things.” Her son Louis Paul’s home, a large two-story home, at one time housed twelve Mexican families, and was badly misused and stripped. The large parlor and living room were used to stable the horses of the Revolutionists, planks being put on the front steps to bring them in. Her home, a neat little three roomed adobe, stood just a few yards away.

When the first war storm passed over, Louis Paul sent some teams down to the colonies and told the driver to bring back anything of hers he could find. When he came back that was all he had on the wagons, for nothing had been molested. She had trunks of clothing, bed linen, and table linen, quantities of dried fruit, and preserved fruit. Elmer said that it did not look as though the door had been opened, although it was unlocked.

She was a brave woman. The afternoon the Rebels came into town, one of them went to her clothesline, which was made of rope, and cut it so he could lead away a horse belonging to Roy Clawson. Disregarding the fact that the rebel had a gun and a knife in his hand, she went out and demanded that he return it. He did.

The Exodus occurred in late July 1912. The Saints went first to El Paso where they received temporary help. They were then encouraged by the government to go where their relatives were or someplace where they could start making a living. Her son Louis Paul moved his family to Binghampton near Tucson, where some of the refugee Saints were making a colony. He built a nice one-room place for her near his own. She didn’t want to be a burden to anyone.

Although she spoke English, she did all her reading and praying in French. She was intuitive, and at times would ask us if something had happened. When we asked her how she knew, she would say, “I knew it. I dreamed it.” She died on July 19, 1923, at Binghampton (now in Tucson), Pima, Arizona and is buried in the Binghampton cemetery.