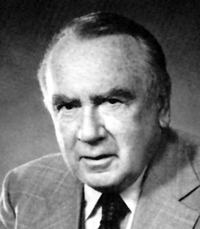

6 Nov 1913 – 16 Sep 2007

Husband of Lucy Elizabeth Cardon

2007 Surrounded by children and grandchildren, Calvin Lewellyn Rampton, Utah’s 11th governor, passed away peacefully and without pain the evening of September 16, 2007. We invite you to join us in celebrating his remarkable life.

Cal was born in Bountiful, Utah on November 6, 1913 to Lewellyn S. and Janet Campbell Rampton. Following his graduation from Davis High School in 1931 his plans for college were dramatically altered by his father’s sudden death. To support his mother, brother Byron and sister Virginia, he took over the family’s automobile business.

The sale of this business in 1933 allowed him to enroll at the University of Utah from which he graduated in 1936. Cal then attended George Washington Law School in Washington, D.C., where he studied at night to allow him to work full time as administrative assistant to Congressman J. Will Robinson.

It was while in Washington that he met and fell in love with his life-partner, Lucybeth Cardon. They were married in 1941. A move back to Utah was followed by the birth of daughter Margaret (Meg). Their union would ultimately yield three more children, Janet, Anthony (Tony) and Vince.

The onset of World War II would suspend family and professional responsibilities as he served in Europe until the war’s end as Chief of the Army Claims Commission in Paris where he obtained the rank of major. He would ultimately become a full colonel in the Army Reserve.

Following the war, he returned to family and the practice of law. His specialty of civil trial practice earned him a fellowship in the International Academy of Trial Lawyers. Having contracted a chronic case of the political virus, Cal’s life became periodically punctuated with candidacies as a Democrat for various political offices. These misadventures uniformly ended in defeat until, in 1964, he was elected governor.

His life would never be the same. Progressive in his philosophy, pragmatic in his approach, and compassionate in his manner, he soon enjoyed the admiration and support of the electorate, and he was elected to and served three terms from 1965 to 1976.

Education formed a cornerstone of his administrations. He believed that the pathway to our future passes through the education of our young.

His competence was recognized far beyond the borders of Utah as he was entrusted with numerous regional and national responsibilities, including heading up the Education Commission of the States, the National Governors Conference, the Four Corners Regional Council and Council of State Governments.

Of perhaps greatest satisfaction throughout his years of public service was his opportunity to share with Lucybeth, measure for measure in their meaningful associations with the people of the State of Utah.

As to leisure, and notwithstanding a swing that couldn’t break an egg, Cal’s great passion was golf. There was nothing that he relished more than a game of golf with his cohorts at the Country Club, followed by libations and a game of gin rummy.

The Alta Club was his choice for political dialogue with the Damned Old Democrats.

He was also an avid reader until eyesight failed, favoring biographies and mysteries.

Following his retirement from public office he returned to the practice of law at Jones, Waldo, Holbrook and McDonough where he practiced until he was 75.

All in all it was a wonderful life.

Cal was preceded in death by his wife Lucybeth and daughter Meg. He is survived by daughter Janet Warburton, and sons Tony (Irene) and Vince (Janice), 15 grandchildren and 10 great-grandchildren and counting.

We would like to extend our warmest gratitude to the caregivers at Care Source. They provided Dad with comfort, care and dignity throughout his stay.

Governor Rampton will lie in state at the Governors Mansion, 603 East South Temple, on Thursday, Sept. 20, 2007, from 12 noon to 4 p.m. Public is welcome.

Services will be on Friday, September 21, 2007, 11 a.m. at Parley’s LDS Stake Center, 1870 East Parley’s Canyon Blvd.

The family will welcome friends and associates from 6-8 p.m. on Thursday evening, September 20, 2007 at Larkin Mortuary, 260 East South Temple, and one hour prior to services on Friday at the stake center. In lieu of flowers we would suggest contributions to KUED or the charity or educational institution of your choice.

Deseret Morning News Aricle

Utah’s longest-serving governor, Calvin Rampton, dead at age 93

By Bob Bernick, Jr. and Lynn Arave

Deseret Morning News

Published: September 17, 2007

Calvin L. Rampton, 93, Utah’s 11th and longest-serving governor ever, died Sunday. Funeral services are planned Friday at 11 a.m. at the Salt Lake Parleys LDS Stake Center, 1870 E. Parleys Canyon Blvd.

On Aug. 8 he suffered a stroke and earlier had been diagnosed with cancer. He was in hospice care, where family joined him Sunday after being alerted to his failing condition, said daughter Janet Warburton. Son Tony Rampton added, “This was not a shock and he passed away peacefully and without pain,” he said today. “We were all there.”

Son Vince Rampton said his father was in and out of conscicousness during the afternoon and passed away a little after 6 p.m. “He gave a little smile and stopped breathing.”

To a generation of Utahns, Mr. Rampton was simply “the governor,” because of his 12 years in office.

Mr. Rampton served as governor from 1965 to 1977, winning three four-year terms. By many accounts, he brought Utah’s government into the modern fiscal era, initiating the first major bonding/building program in the state’s history and restructuring government for the first time since statehood. Much of the University of Utah’s “new” campus, as well as other public higher education campuses, were constructed through his efforts. He started “Rampton’s Raiders,” a group of volunteer businessmen who traveled the United States drumming up economic and tourist interest in Utah.

But what most people will likely remember about Rampton was his slow-talking, congenial style. While most called him governor to his face — even after he left office — they referred to him as simply Cal when talking outside his presence. He was rarely seen in public as angry or even perturbed.

A Bountiful native, Rampton retired from government service in 1977, returning to a private law practice.

Having ended his public career still loved by most Utahns, one wouldn’t believe Rampton’s political beginnings. He was rejected for office time after time. He lost three races for the state Senate, a race for state Democratic Party chairmanship and one that would have made him the Democratic national committeeman from Utah. He lost the Democratic U.S. Senate primary in 1962. In fact, he lost so many races in so short a span that some wondered what he was thinking when he got in the 1964 governor’s race.

But it was a landslide Democratic year. Lyndon Johnson took Utah on his way to the presidency, the only time in the past 40 years that a Democratic presidential candidate carried Utah, and Rampton swung into office.

He ran on a pledge to change Utah government, and he didn’t wait long. He proposed an ambitious bonding program of $67 million — an outlandish amount in the mid-1960s considering that 30 years later the Legislature is arguing over $100 million bonds.

He put together what came to be called the Little Hoover Commission, which recommended vast restructuring of state government, the first such effort since statehood in 1896. In 1964, more than 150 state agencies reported directly to the governor. Little Hoover recommended the 150 be bunched up into 10 departments, and Rampton pushed the change through a special legislative session.

After eight years in office, many wondered if Rampton would break precedent and run for a third term. To the surprise of many, he decided to do just that. Even though Utah was beginning a hard swing toward Republicanism, Rampton won re-election in 1972 by his largest margin ever, even though then-President Richard Nixon, a Republican, took Utah in a landslide.

Later, Rampton was to say the last term probably was a mistake, that it cost his family too dearly. His wife, Lucybeth, suffered from clinical depression in 1974 and later Rampton said he’d lost some of the drive needed to conduct state business at the highest level.

Rampton was born and reared a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and counted many of its leaders as personal friends. But he did not always follow all of its precepts. More than one reporter found Rampton in private enjoying a large cigar. In one of his rare scrapes with public opinion, it was discovered during his 12 years as governor — and in fact in previous administrations — that agents for liquor companies wishing to do business with the state were giving free samples to the Liquor Commission, and that some of those samples were passed along to the governor’s mansion and used to officially entertain visiting dignitaries. Rampton defended the practice, saying it was perfectly legal. But, as he wrote in his autobiography “As I Recall,” much was made of it in the press.

He was also named “outstanding public administrator in Utah” by Brigham Young University in 1972 and he and his wife, Lucybeth (who died at age 89 on Jan. 23, 2004.) were honored by the National Conference of Christians and Jews with a “Brotherhood” award in 1973.

In retirement, Rampton became a partner in Jones, Waldo, Holbrook and McDonough, one of the state’s largest legal firms. He kept his hand in politics, lobbying the Legislature for various clients — including the Newspaper Agency Corp., the publishing arm of the Deseret Morning News and Salt Lake Tribune — and was chairman of various political campaigns. He didn’t mind speaking out as an emeritus Democratic leader, as he did in the 1991 state party chairmanship race in which he said organized labor had too great an influence in party politics , a comment that generated a mild furor.

Even in his 90s, he still worked at a law office one day a week.

Mr. Rampton was born Nov. 6, 1913 to Llewellyn S. and Janet Campbell Rampton of Bountiful, the oldest of three children.

His father and his uncle ran a car dealership/garage in Bountiful, first selling Studebakers, then Fords, and finally Chevrolets. Bountiful had a population of about 1,500 back then, and Rampton said that as a boy he knew almost everyone in Davis County.

As a young man, Rampton remembered visiting a neighbor’s house, hearing a celebration and learning that his young friend’s father, Charles Mabey, had just been elected governor. He didn’t know what that meant. He asked his young friend who the “governor” was. “‘He’s the boss of the whole state,”‘ Rampton recalled his friend saying. “That was a statement I would later find was a great exaggeration,” Rampton joked years later.

Mr. Rampton graduated from Davis High School in 1931. In the fall of 1931, his father died suddenly. Rampton, only 17, helped run the family business for two years, before he and his uncle sold it in 1933.

While he approved of general LDS Church religious philosophy, he decided not to go on a church mission because he didn’t think he “had enough faith in some dogma to teach it.”

Mr. Rampton got his first real taste of politics in 1932, when he became excited with Franklin D. Roosevelt’s run for president. A family friend was Davis County Democratic chairman and he appointed Rampton assistant party secretary. Rampton said he worked hard for Roosevelt, passing out handbills and going door-to-door. Years later, Rampton would describe himself, as many other Americans of that era did, as a “Roosevelt Democrat.”

Mr. Rampton entered the University of Utah after selling the family business. He graduated and attended George Washington University in graduate law studies, then graduated from the University of Utah Law School, where he became a “reader” for professor Willis Ritter, later a well-known federal judge in Utah. After finishing his undergraduate degree from the U., Rampton applied to be administrative assistant to Rep. J.W. Robinson, D-Utah, and moved to Washington, D.C., serving Robinson from 1936 to 1938. Rampton was elected chairman of the Administrative Assistants Association in a race against Lyndon Johnson’s younger brother, Sam Houston Johnson. The young Utahn attended George Washington University Law School at night and on Saturdays.

Even though he still had a year before getting his law degree, Rampton returned to Utah in 1939 and was elected Davis County attorney, serving from 1939 to 1940. At that time a county attorney didn’t have to be a member of the bar. It was a part-time position that paid only $75 a month. Until his election as governor 16 years later it was the only elective office he ever won.

Mr. Rampton well remembered the first real case he tried as a prosecutor. It involved a man charged with a number of severe traffic violations. The offender was tried before Joseph Sill, father of soon-to-be LDS general authority Sterling Sill. Joseph Sill at the time was in his mid-70s, a non-lawyer serving his first term as a justice of the peace. Justice Sill was running for the Utah Senate in 1940 as a Democrat, and Rampton had also filed for the office, having decided not to run for re-election as county attorney. The defense attorney was a well-known Salt Lake attorney. After Rampton finished questioning his last witness — and believing he’d done a fine job for a beginning lawyer who wasn’t even a member of the bar — he jumped to his feet shouting, “I move all charges be dropped.” Sill, duly unimpressed by his Democratic primary opponent, immediately replied, “I second the motion.” The defendant was freed.

Mr. Rampton, having decided not to seek re-election as county attorney, instead worked for the Democratic attorney general candidate who promised him a job as an assistant attorney general should he win. At the same time, Rampton worked for a State Senate seat, but not very hard. He thought he had an easy win, but he lost to his Republican opponent by less than two dozen votes. “I learned a valuable lesson. I had more relatives than that who hadn’t bothered to vote,” he said in retrospect.

He joined the Utah National Guard as an enlisted man in 1932. He rose through the ranks, becoming a sergeant and then a first lieutenant in 1937. When World War II broke out he was called up and glad to serve. But he’d had a severe case of pneumonia as a freshman in college — he nearly died — and somehow his Army medical records were mixed up with those of a man who had a bad heart. After only several months of active duty, Rampton was shipped home as too ill to serve, Army doctors stubbornly refused to admit they had the wrong records. It took Rampton nearly a year of writing letters to Army officials to get the matter straightened out. He was finally appointed to the Judge Advocate’s office in the Army. He went into active duty in January 1942, shipped to Europe in 1944. After the war he served in the U.S. Army Claims Commission in Paris. He left as a major.

Mr. Rampton returned to Utah following the war and worked part time in the attorney general’s office and opened a three-man law firm in downtown Salt Lake City. He started a tradition of running — and losing — for various offices along the way.

Winning the governorship in 1964 wasn’t a shock to Rampton. After all, he figured during all of his races that he’d win. He just hadn’t. On election night 1964, after the parties and congratulations, Rampton and Lucybeth settled down in front of a fire in the living room of their eastside Salt Lake home. Musing a bit, Rampton said softly out loud, “What if I disappoint them (Utah citizens)?” After a short silence he said, “But I won’t.” And he didn’t.

Mr. Rampton often pointed out that his wife, a granddaughter of the late Anthony W. Ivins, a former First Counselor in the LDS Church First Presidency. was one of his greatest assets. He married Lucybeth in 1940 and they were together for some 63-plus years. He met Lucybeth during his two-year stay in Washington, D.C. They were the parents of four children, two sons and two daughters.

Generally, his popularity stemmed from being a progressive governor and one who was considered trustworthy and truthful.

Although his state building construction program required an increase in the individual income tax and corporation franchise tax, he helped completely eliminate the state-wide property tax in 1974.

Mr. Rampton made thousands of appearances as governor, from the major public gatherings to the minor ribbon-cuttings. His aides claimed that he had visited practically every city, town and hamlet in the state and was acquainted with the problems and aspirations in each one.

One goal he failed to achieve as governor was his effort to repeal or modify the state’s Right-to-Work law.

He believed his biggest defeat while governor was the failure to pass a land use act in 1976. In retrospect, Mr. Rampton believes the lack of that bill meant needless suffering during the disastrous floods and mudslides of 1983-84.

As a member of the LDS Church, he had at one time taught Sunday School and had also served as an assistant Scout master. His hobbies included hunting, golf and fishing.

In his post-governor years. he wrote his autobiography, “As I Recall,” published by the University of Utah Press in 1989. He also continued to work doing consultations in law at the Main Street offices of Jones, Waldo, Holbrook and McDonough. He spent many of his lunch hours at the Alta Club, keeping current on Utah affairs. He served on the UTA board and the KUTV, Channel 2 board, as well as other local boards.

A mini-stroke in the late 1990s slowed his golf game, but he remained articulate. He and his wife also took a foreign trip every year after he left office until her passing.

Salt Lake City Cemetery, Salt Lake City, Utah