20 May 1822 – 25 Jul 1882

Daughter of Philip and Martha Cardon

THE SISTER WHO STAYED BEHIND

COMPILED BY BROOKIE PETERSON AUGUST 2003

Anne Cardon was born the 20th of May 1822, the first child of loving parents, Philippe and Marthe Marie Tourn Cardon. She died sixty years later. She was the only living child of the family who did not go to America. Anne was the oldest of nine children. When she was nine years old her four-year-old brother, Barthelemi died. When Anne was twelve years old her little sister, Louise, was born on Christmas Day, but before the young girl turned five, she too passed away. So, you can see, Anne was “acquainted with grief” from an early age, yet because of the loving kindness in her family, she had many happy times also. Besides her two siblings who died as children, she had four brothers and two sisters who all outlived her yet moved away from her and lived on the other side of an ocean on another continent. But, to begin at the beginning, as far as is known Anne didn’t write her life history or any part of it. The following points of her life have been determined from the history of her sister, Marie Madeline, from five letters written by Anne, or for her by someone else, to her family and from facts gleaned from Church and public records. Her daughters have also written letters which shed light on their mother’s life. Anne was born in a village called Borgata Cardon [see appendix A] located in Prarostino, Torino, Italy. [However, as a country, Italy did not exist until 1861 when Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia proclaimed it the kingdom of Italy and became its king.] Her birthplace is in an area known as the Piedmont in the foothills of the Cottian Alps. It is situated in the north of Italy near the present-day cities of Turin and Milan and even closer to the town of Torre Pellice. Her ancestors were French speaking and belonged to a protestant religion known in English as Waldensian, in French as Vaudois [Voh dwah] and in Italian as Valdesi. This group of Christians was much persecuted because of their beliefs which were different from the dominant Catholic religion. For a history of the Waldensian people see Appendix B. In 1848 there was an Emancipation Edict which gave Anne’s people civil rights, the right to education and an equality before the government. However, there was still prejudice against their religion although its outward manifestation no longer took the form of kidnaping children and, forbidding further contact with their parents, placing them in Catholic homes. This despicable practice, among other heinous acts of cruelty, had been common for centuries. Soon after the Edict, the Cardon family were able to move off the rugged mountain and live in the valley near San Secondo. We know little of Anne’s growing up years but can surmise that they were years of hard work to help her parents with the younger eight children. Her sister Marie tells of their religious training. “The only book which my father had was a Bible which then was over two centuries old, handed down by his ancestors. I well remember the time when all our family would gather around my mother and father each night, just before retiring, and listen to him read a chapter in whole or in part from the Bible. After he had read, he would review what he had read and explain to us little ones many good principles.” In her letters, Anne speaks of her feelings about her parents. Writing to her sister in 1873, just after her mother had passed away, she describes her mother’s character and the love she exhibited towards her children. “You can understand very well how much the death of our dear Mother afflicts me. To me it seems that she is always before my eyes. With her great goodness that God gave her she never stopped showing us the way to Heaven. With a sweet spirit, and with charity. She didn’t weigh our mistakes, but she asked forgiveness from God, warning us with sweetness and tears. My dear Sisters, I thank you infinitely for the attention you have given to me in sending hair from our dear Father & our tender Mother. [It was a common practice to send hair which was an intimate and easily preserved object connected to a loved one. Often it would be mounted and framed or put in a locket.] More than that, I see that you think of me, and I hold dear these precious hairs. Even more precious because they are from our dear Father & Mother, who have been so far away, and that they are in my hands.”In a letter to her sister, written in 1881, the year before she died, she expresses her love and admiration for her father. From it we can know that she must have had a largely happy childhood and youth, feeling peace and security because of their wise and loving direction. “I will never be able to thank you enough for the good details you give us of all my dear family and my dear, dear father. (Philippe Cardon). How I would like to see him, hug him and take loving care of him, he who took care of me like the apple of his eye. Ah, my memory and my heart do not fail me as far as affection and filial respect are concerned. It is with the strongest memory, the greatest respect, the sweetest and most thankful affection that I remember his fatherly tenderness, his instructions, his counsel, his wholesome and corrective counsels. They will always be the traveling companions …. of my pain, my intimate friends in my solitude. His good instructions were blessed by the grace of God in Jesus Christ for my soul. May God’s divine blessing rest on him. May the Lord God be his strength and his shield.”

When she was twenty-five years old in 1847, Anne married Jacques Rivoir, who was nineteen years older than she. This marriage only lasted ten years before he died, leaving her a widow at age thirty five. It would not be possible to give a complete version of Anne’s life without referring to the dream her sister Marie had as a child. [See Appendix C]. Partly because of her father’s knowledge of this dream and its look into the future, he was open to the teaching of Lorenzo Snow and the other missionaries when they came to Italy in 1850. During the year 1852 her entire family–parents and siblings–was baptized into the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. That is the whole family except for Anne; her husband, Jacques Rivoir, was antagonistic toward the new religion, and forbade her to visit her parents’ home or to have anything to do with the Mormons. It is said that, at the time, she was receptive and sympathetic towards the religion her family chose. Her sister reported that she wanted to hear the elders explain the gospel; however, in her letters written two decades later, it is clear that she has misgivings about the practice of polygamy. The names of her parents have already been mentioned. Her brothers and sisters, in birth order are second after Anne, Jean–also the name of her paternal grandfather, born 1824; Catherine, 1829; Philippe-later Louis Philip, 1832; Marie Madeleine, 1834; Jean Paul-later Paul, 1840; and Thomas Barthelemy, 1842. Anne’s husband, who had objected to her even learning of the gospel, died just three years after her family emigrated to the United States. She was left with two small daughters, Marie age seven and Anne or Annette, age two. Three years later, she married her second husband, who was her cousin, Barthelemy Gaudin, son of her father’s sister, Martha Cardon Gaudin. He must have been good to Anne’s daughters as her older daughter, Marie, speaks very lovingly of him and calls him her “second father.” Another factor in Anne’s day to day life was a permanent house guest – Aunt Marthe, who was very handicapped and so required hours of time for her care each day. Aunt Marthe was the sister of Barthelemi Gaudin, Anne’s second husband. She is also the sister of the wife of Paul Cardon, Suzanne. She lived with Anne and Barthelemi for over a decade, and later, after Anne’s death, lived with her daughter Marie for more than another ten years. They continually struggled to take care of her financially and physically. Later letters [1888] from Marie describe best for us Marie’s own life and work and the great trial Aunt Marthe posed to their livelihood. “As for me, I’m rather well, and I work as much as I can in order to raise my five children, who are still quite small, and to take care of your poor sister Marthe (Gaudin), whom you can’t help but feel sorry for. Last winter she had the misfortune to fall on a stick of wood that poked out one of her eyes and caused her terrible suffering for a long time. She is becoming fatter and soon will not be able to stand up. I have to wash her and take care of her like a little child. So, my dear relatives, pray God for me that he gives me much patience. I still have a lot to do, especially since my little girl was nearly always sick since the death of my dear husband. Then we had a very long and difficult winter. Papa (Bartholemy Gaudin) was also feeling poorly. He often complains of having pains in his arms. He can scarcely work, even though he does everything that he can. He is no longer very strong and can neither plow nor even work in the vineyard, which means that to stay here I need a good domestic, and I would really be thankful if you could help me pay for one. …. I can only thank God for having such wonderful relatives, and I hope that He will keep you a long time in good health.”

To understand something of the country and times in which Anne’s life was lived it is enlightening to read a commentary on the reason most of the emigrants chose to leave their homes and farms to venture to the new world. Devastating crop failures struck in the 1850’s. A pastor wrote: “It is dreadful; if we do not receive substantial subsidies our people will starve by the hundreds…most of our families are ruined. Some have six, eight or ten children – all of them dependent, with no prospect of food for the next day. So great is the poverty that most of our people are on the brink of an abyss –[crops] have failed for four consecutive years. – our villages are destitute.”

Population increase, agricultural crises, debts and extreme poverty; all pointed to emigration in the interest of survival. One emigrant who sailed for Argentina said, “Neither the love of adventure nor the prospect of wealth drives us to take our families to remote countries we do not know and from which none of us will probably ever return. No, poverty, suffering, and hunger are the forces that expel us.” You Are My Witnesses – Giorgio Tourn and Associates page 235-6

Quoting from Anne in 1871 “You must know that among us, namely in Europe everything has changed; everything has an excessive price, from the meats to the grains. Cows that before sold at the price of 120 Franks today sell from 350 to 400 Franks, fat pigs from 14 to 16 Franks and the big ones from 25 to 40 Franks. “We must tell you that here we have had our own worries and our own concerns. Our uncle Jacques has had the misfortune to burn down his house; they are left with almost nothing; they have to stay here with us, and many other things have happened. Did I not tell you that here grain is sold at the price of 8 Franks per bushel, potatoes are more than one Frank, fruit and other foodstuffs are sold in proportions… anyway everything has changed in price. Everything goes at a great rhythm, everything runs fast, the time as well as the money.”

As before mentioned, many of Anne’s feelings are expressed in her letters to her sisters or brothers. We have no record of any exchange of letters between them for seventeen years after their emigration. Perhaps the cost of sending mail was prohibitive. Some things Anne writes in the earliest letter we know of [1871] would lead you to believe they had little or no communication during all those years. “My dear sisters, I want to tell you that it gave me great pleasure to receive your letter. … You are manifesting in me the desire to receive your news more often. We are surprised to find that the letters can get lost. Many letters have been addressed to you but you have received only that one. “Does the great railroad that you have from New York to San Francisco pass near your city? Tell us also what you do and if you live in the city or the country. “Thanks to God we are well just as we see that you are. It gives us great pleasure to see your photographs, especially to see your beautiful clothes, your beautiful attitudes, elegant, and the beautiful hair you have. Here we find that neither our hair nor our look conserve themselves as well as yours; this shows that good air is there among you.”

Her last comment — attributing their beautiful hair and look to good air is fascinating, the fact probably being, that she had a life of drudgery eking out a living from vineyard and farm and taking care of Aunt Marthe while theirs were lives of hard work, but of better quality. Anne was a very spiritual person. She understood many gospel truths. Often in her letters she speaks of the Savior and her Heavenly Father. However, if in her young married years she was inclined toward the Church, she had a change of thought about one of its practices as she matured. Quotes from a letter written in 1871 show this. She must have just learned of her father’s taking a plural wife some eight years after the marriage. “I must tell you that the last letters that you wrote to me gave me great pleasure but at the same time sorrow; can you understand this? It has been years that I have [not] known what our father had done ….. and so violate the seventh commandment of God but what do you want? We cannot judge him nor condemn him, but we can regret it and this shows that God did well at the beginning to create a man and a woman, in his great wisdom; and who are we to change His Statutes and His Laws? “You tell us nothing of Jean and Philippe, you tell us nothing of Barthelemy; do they as well have many wives? I have always had a great disgust for this … polygamy. It seems to me that we can be children of God through Jesus Christ, following His commandments, and if those missionaries that took you away had never talked about polygamy but only of baptism; that is following the ordinances of the Lord, because ours comes to us from Rome (this we know for certain), they would have had hundreds of people instead of a few that accepted them.”

Most of their letters were written for them by someone else; apparently, it was hard for them to write, although from several clues I believe they knew how, but perhaps their ability was superficial. It may have had something to do with writing in Patois which was what they called the dialect they spoke. “You ask me how I can be happy without the presence of my family, but I can tell you that most of my time I am sick to know that I wasn’t able to follow you and our dear parents.”

Writing 17 years after their departure, Anne writes of her lifelong dream to join her family in America. Late 1870’s “You know that we have a problem with Marthe, our sister and sister-in-law. We fear that she will not be able to face such a voyage, because she is too fat. Barthelemi says it would be too difficult to travel only us two with her, because we would have to help her get on and off the train and from the boat, just like you would have to do for a baby, and then our conscience impedes us from leaving her here alone, but also we fear that if we leave her here with what little land we own, she would not be able to take care of it. Therefore, now we have taken a decision, and now we all wait for your answer to know if we can come or not. “Regarding our trip, we could pay only one half and no more. We pray you, tell us if you think it will be possible for us to have land because here we sell all that we have; we are forced to do it to pay a part of the voyage. When we will be in America, we will be under the grace of God and also under yours.”

The following letter was composed by Anne about one and one/half years before she died. 1881 “We would all like to come, but for all of us to come would make nine people. Marie has a baby boy to wean and Annette also has a baby girl to wean; with their husbands they make six plus the three of us. “To come, without counting the babies, it would cost us about 5,000 Franks. In coming there, we would like to have land that doesn’t cost too much, that is fertile and not too far from you. If we have to come and live far away, without seeing each other more than we do now nothing would change. We are coming to be with you. We could divide the cost of the voyage. Now I’ll explain the reason. Barthelemy and I still have some debts and our land is not worth much. Marie could sell but even in Milan, land isn’t worth much, and her husband is the family son [probably means the oldest or birthright son or possibly the only son of his parents.]. Annette also has her land in Milan, and her husband is a bricklayer by profession and the family son as well. “When we want to sell, we must do it at a cheap price. Dear family, we would come with pleasure, but we have need of time to sell and gather the money necessary. Is polygamy still there among you? And even if it is, will we be obligated to practice it? Written to her sister Catherine Cardon Byrne, by Jacques Constantin of Collaray: From “Your most affectionate Anne Cardon Gaudin. My husband is Barthelemy Gaudin of Balcoste and I have two wonderful daughters Marie and Anne Rivoir.”

Anne, the mother, died July 25, 1882. This is an account of her death written by her daughter Anne, signing Annette, the diminutive form of Anne. It tells the family in America of her mother’s last days. Prarustin August 8, 1882 “Very dear and well-loved family: Uncle and aunt and cousin [masculine] and cousin [feminine] and especially to our dear grandfather if he is still living, “It is with great sorrow that we write you a few lines to inform you of the long illness of our dear mother — 3 months when she was ill before taking to bed and then 4 months in a bed of pain of which the 8 last days the violent pain almost surpassed her strength, but she endured her torments with a great patience. She said it was nothing in comparison to the suffering which Jesus Christ had on the cross for some hours before his death. She got a stomachache which did not leave her until her death. “She said that she would have liked to be healed physically in order to see you in her last days. As she saw herself approaching death, she said that she would like to be able to run to meet death in order to more quickly be close to her Savior and to her dear mother. At last, she died the 25th of August [Should be 25th of July; she writes this letter on the 8th of August] at 2 o’clock in the afternoon with her bed surrounded by her two daughters and some other women with us. Well, I hope and have a firm belief that she waits for us at the feet of Jesus where we will find ourselves soon all together. I think that my sister will write to you more of our dear mother; pardon all our faults and don’t forget to write to us I beg you. “I declare myself [to be] for life your niece Rivoire Annette”

The daughters, Marie and Annette, continued to live in poverty, to long to join their American relatives to the end of their lives. Living with Marie is her second father, Barthelemi Gaudin and his sister Aunt Marthe Gaudin, who continues to be a great problem for them as she was for their mother, Anne. December 28, 1888 “And now I will send some details on me and my family as you ask me to. My Papa [in another letter she says “your cousin, my second father Barthelemy Gaudin and his poor sister idiot–Martha Gaudin] lives with me since more than a year…. poor Aunt Marthe continues to be in a deplorable state. She fell recently and the only eye that she has left was so badly damaged that I think that she doesn’t see any more at all. She has to be fed like a baby, and I dress her, and tend her as if she only had a few more months. “This is a terrible trial that God sends us, and you can’t imagine the sad condition of the poor aunt, and of all the trouble that she gives me. Without her, I could with my children look for another house, sell my land, and find an occupation that would procure me the daily bread. But no one wants to take me with the unfortunate Aunt Marthe, and that is why I am obliged to continue to live in the house where I am. I would be very grateful to you if you could send me something which would help me from now till next summer and would provide for the needs of the aunt. I have tried three times to get her into a charitable establishment, but they absolutely will not take her because of her state of complete dependance.” Your niece Marie Gonnet

And [writing] for her: Emma Pons The godmother of Marie Rivoire was Catherine Cardon who was her mother Anne’s sister and the 4th child of Philippe and Marthe Marie Tourn Cardon. Showing her immense gratitude and her feelings of love and dependence on those in America, Marie writes some years later: 4 April 1892 “Believe it dear godmother that it is impossible for me to describe to you the gratefulness which I feel in thinking of you who were so good to me at the time of the death of my dear mother and the 500 francs which you sent to me contributed greatly for me and I weep in thinking of so many of your good deeds of which I have been witness myself and pray that God will bless you and preserve all of you a long time. I see that you have always been very good to me, and I am extremely grateful to you for that. I find myself at present still at La Tour [Torre – Pellice] on this farm. I still have Marthe. Marthe has been my little one and my charge, but what would you? I must have patience and be content with my lot. But I assure you that I must have enormous patience to tend this miserable one. I went to visit my sister yesterday and she is also very unfortunate with 4 or 5 small children. She tells me to greet aunt Madeline and receive from the bottom of our hearts our sincere greetings. Your Affectionate Goddaughter,” Marie

In closing the small window of opportunity, we have had to view Anne Cardon’s life, let me mention again the high priority faith in Jesus Christ and God held for her. It seems that many of the Waldensians had the Gift of the Spirit called beholding of angels and ministering spirits [Moroni 10:14] for they had in their histories, records of dreams and visions. Some were given at an early age as was her sister’s dream, Marie Madeline, when she was six or seven years old. Anne wrote this in one of her letters [1873]. “…when I was 13 years old, I saw in a vision how God guided you and me at the same time. I heard a great voice that said to me ‘through fasting and prayer many sins will be forgiven you.’ I hope that God will — give us strength from his Holy Spirit so that we can say as St. Paul, when he said, ‘Oh God how happy I am to have learned to live in the state in which I find myself.’ “And it is the same for all of us to be happy in the state in which we find ourselves. It is enough that we live worthy of being among the elect. Seems to me that, we should all pray to God on our knees with fasting. “I am not coming to America to search for the riches of this world, but I go to find the peace of my soul, and also because my two daughters have always desired since their infancy to reach you one day. This has always been their greatest desire. [Of course, she never realized this dream, although she writes as if it is about to happen.] “Well, by the grace of God I feel that I am one of his children that he has redeemed with his precious blood. Faith, hope and love are not feeble and spiritless words for me. My hope is in God, who by the merits of his well-beloved son, our only Savior, gave us a celestial inheritance. [He] will be my strength, my support, my light and my everything for time and eternity.”

To me, this is the story of a valiant woman who loved God all her life and also had great love for her family. During the 1990s some of the extended families were able to contact some of her descendants. All of them were descendants of Annette, her younger daughter. The older daughter, Marie, lost three children to death when they were very young; her son Jean Gonnet, who lived to adulthood, died without leaving children. Annette’s descendants — grandchildren and great grandchildren know something of her but know no stories nor any facts about their great-great grandmother, Anne. She has been forgotten because of lack of information about her. In the summer of 2002, when a group of family members visited Italy, they met several of these descendants. They were very gracious and interested in their history. They also asked for three copies of the Book of Mormon and one couple have since had the missionary lessons. It is hoped that in time some of them will accept the gospel message. Surely this would bring great joy to Grandmother Anne.

DATES RELEVANT TO ANNE’S LIFE

| 1822 | 20 May Anne Cardon, [first child] daughter of Philippe Cardon and Marthe Marie Tourn his wife, was born. |

| 1847 | 30 September Anne 26 md Jacques Rivoir 44 at Prarustin |

| 1850 | 15 December Anne’s first child, Marie Rivoir born. [Father Philippe and Marthe Marie’s first grandchild] |

| 1855 | 7 Jan Anne’s daughter Anne Rivoir [known as Annette] born in Prarustin |

| 1857 | 5 February Anne’s husband Jacques Rivoir died |

| 1860 | 29 November Anne md cousin Barthelemy Gaudin. They had no children. [Barthelemy was the son of Marthe Cardon and Barthelemy Gaudin. Marthe was sister of Father Philippe and the senior Barthelemy was the brother of Jeanne Marie Gaudin Stalle, Father Philippe’s second wife.] |

| 1864 | 20 February Marthe Cardon Gaudin, sister of Father Philippe, died |

| 1874 | 16 April Anne’s daughter Marie 24 married Jean Gonnet |

| 1878 | 2 May Anne’s daughter Anne [Annette] md Jean Pierre Constantin All living descendants of Anne have come through her daughter [Annette] Rivoire Constantin. |

| 1879 | 24 September Anne’s grandchild Jean Michel Gonnet, son of Marie, was born. |

| 1882 | 25 July Anne died. |

| 1895 | Probably January Marthe Gaudin died. She is the “Aunt Marthe” in many of the letters, also known as Martrota; she is the sister of Anne’s second husband Barthelemy Gaudin. Marthe Cardon Gaudin who was sister to Father Philippe, who died some thirty years earlier was her mother [1964]. |

Marie Rivoir Gonnet: On church records the spelling is Rivoir, but they sometimes spelled it Rivoire. Marie had two more Gonnet children.

| 1884 | Jacques died at age 1. |

| 1886 | February Her husband Jacques died. Her son Jean was 6 years old and her daughter Marie Alice, 8 months old at the time. |

| 1889 | Marie Alice died at age four. |

| 1890 | married 2nd Bernardino Francese. They had one son Alberto, who died age 3. Husband #2 died. |

| 1892 | married 3rd Barthelemy Volle who died before Marie. |

| 1895 | Her letter says she is married to a man named Pinot. |

| 1931 | Marie, who never got to come to America, died in Italy. |

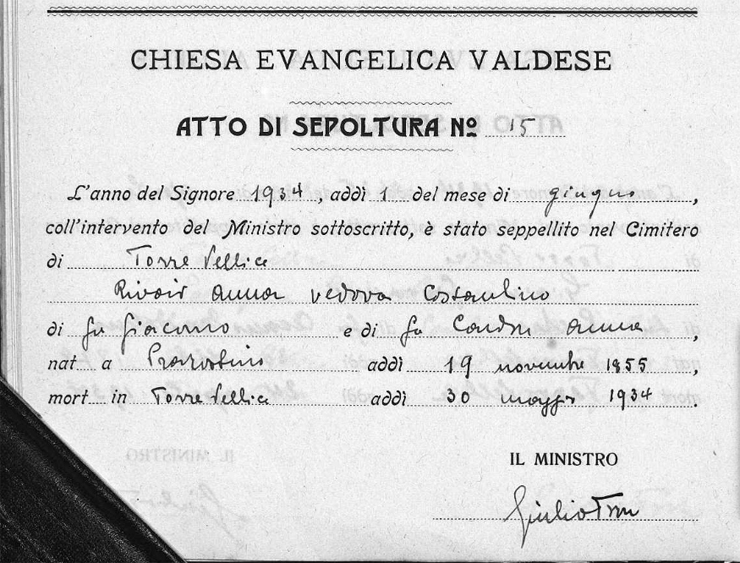

The death date for Annette Rivoir Costantino was not established at the time Brookie Peterson compiled this report. She died as Rivoir Anna widow Costantino, on the 30th of May 1934 in Torre Pellice and was buried on the 1st of June in the Torre Pellice cemetery.

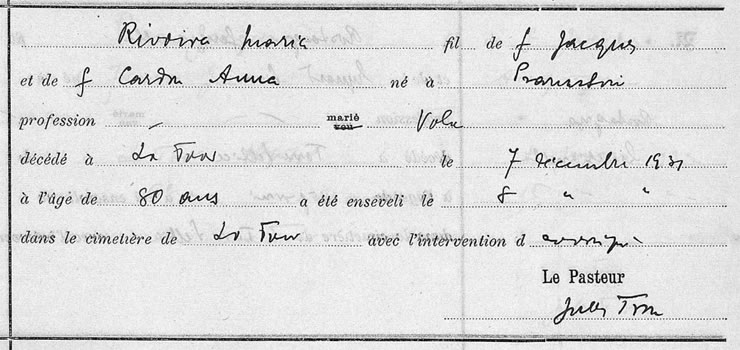

The death record of Marie Rivoire as is the burial record of Anna are in the Waldensian Evangelical Church Records, 1679-1969 and can be found on familysearch.org. Below is photo of Marie’s record.

APPENDIX A

The Cardon Borgata

The Cardon Borgata appears on a map as early as the seventeenth century. Borgata means hamlet or small village. According to the Masters’ thesis of Diane Stokoe page 41, the family of Philippe and Marthe Marie Tourn Cardon lived in the Cardon village prior to the Edict of Emancipation for the Waldensians which brought new freedoms in 1848. It was in that village that Marie Madeleine had her childhood dream. Soon after 1848, as there was no longer reason to hide in fear, Philippe moved his family down to San Secondo di Pinerolo, on the edge of the Piedmont plains where he worked as an architect and stone mason. So it was in San Secondo that the family lived when the father first heard of the missionaries and went to hear the gospel preached. However, the Borgata is the place we identify as their home. There are a number of things to look for in a visit to it. Some of the homes have been restored, and people live in them either year-round or use them as summer retreats. You will remember that in early days, the animals lived on the first floor and the family on the second to take advantage of the heat which would rise16 from the animals and which would make their homes warmer. Take notice of the wild strawberries. Suzette Stale Cardon brought strawberry plants from her home and carried them in the first handcart company. She was a master at drying strawberries. In Arizona, the University asked her to explain her method as the extension division had never been able to do it so well. You will discover that the doors and windows are very small. There are probably two reasons for this. Our ancestors were small people. Also, a portion of their taxes were determined by the size of the windows and doors. The smaller they were, the lower the tax. We should be able to find the outdoor ovens. Marie Madeleine writes that, in Italy, they would bake as much as one hundred pounds of flour and roast meat to feed those who came to their home to hear the missionaries. Near the homes is the symbol of the Waldensians – the eternal flame meaning “keep the eternal flame of the gospel alive.” Off in the distance we can see an old Waldensian temple. Climb up the terraces to get a beautiful view and feel the connection that will come into your heart that our ancestors lived and worked, loved and died here.

APPENDIX B

WALDENSIAN HISTORY FOR CARDONS

Much of the following comes from an article by Ron Malan, “Waldensian History. A Brief Sketch” Available at PFO web site http://homepages.rootsweb.com/~waldense/ All serious historians now agree that the Waldensian movement began in Lyons about 1170. Claims to greater antiquity came much later and are unfounded. These claims seem to have been brought about by a desire to show descent from the time of the Apostles, but they have proven to be incorrect. It is now also universally agreed that the founder’s name was not Peter Waldo; he was never called Peter until some 150 years after his death. The form of his name currently accepted is either Vaudes or Valdes –. We’ll use the form Valdes here, as the “l” sound is maintained in the current name Waldensian and will therefore be more familiar. And, until joining the Protestant Reformation in the 1500s, his followers never called themselves “Waldensians.” That term was applied to them by those who sought to destroy them and therefore carried pejorative connotations. Rather, they consistently referred to17 themselves as the “Poor of Christ,” the “Poor of Lyons,” the “Poor in Spirit,” or more simply “Brothers.” By the middle of the 13th century, they were considered to be heretics and they had to move to rural areas, eliminate public preaching and simply try to maintain their group, not increase it in size. Most of their preachers settled down, married, and raised families. They were no longer inclined to give away all they had, but they came to devote much of their effort to providing for their families, including legacies for heirs. Their wills demonstrate this, yet they still had the attitude of being generous to and caring for the poor. Due to the influence of the reformation, there was a major change in their worship habits and status as a church in the mid-sixteenth century. They began to erect formal buildings of worship, in place of the traditional secret meetings in the open or, for smaller groups, in homes. The openness increased their numbers, but being more visible also increased the persecution they experienced. They began to call themselves Waldensians; though formerly it had been a belittling name used by their persecutors, it now became a compliment. Their pastors or Barba began to be educated–mostly in Switzerland. Up to this time they had been opposed to formal education for the Barba. For the century following the mid 1500’s persecution of the Waldensians became very severe, constantly increasing. There was the massacre of 1545 and in 1630 a terrible plague killed many of their number including eleven of their thirteen pastors. In April 1655, the Waldensians were ordered to quarter the soldiers of the Duke of Savoy in their homes. Early on Easter morning, at a given signal, these troops arose and brutally murdered their host families. This became known as the Piedmont Easter and led the English poet Milton to write his famous sonnet, “On the Late Massacre in Piedmont,” about the “slaughtered saints.” In 1685 The Waldensian pastors were expelled, Waldensian worship was forbidden, and all children were to be baptized Catholics. Following the refusal of the Waldensians to do this, within three days their persecutors killed some 2000 of them. Some 8500 were sent to prisons; most of these died from lack of food, water, disease and poor shelter. Those who remained were sent into exile. Four years later in 1689, those who could, came back to their homelands in what is known as “The Glorious Return.” Persecution continued for almost another 200 years. In the time of Napoleon there was the infamous “home for Waldensian children,” in which kidnapped or enticed children had been raised as Catholics, their parents not even permitted to visit them. There was a long history of child snatching by the enemies of the Waldensians. The purpose was to force the children to become Catholic. They were sometimes taken with18 the knowledge, but not the consent, of the parents and at other times simply abducted. No child wandering on its own was safe. Besides the home for Waldensian children, sometimes they were taken in as a servant to a Catholic family or at times as a family member. In 1848, Savoy which had been a principality became part of Italy, and finally the Waldensians were granted full rights of citizenship. For the first time in centuries, Waldensians could hold public office, choose the profession they wished, and acquire land; and their children could qualify for higher education. But the declaration failed to provide greater religious freedom. Still, it was the beginning of that process. Upon receiving the news, the Waldensian villages celebrated by building bonfires, visible all up the mountainside. It is interesting to observe that Lorenzo Snow was sent to Italy in June of 1850. It could hardly have been a coincidence; had he gone much earlier the Waldensians would not have been at liberty to listen to his teaching. During the last half of the nineteenth century, very hard economic times befell inhabitants of the valleys. This led to emigration. Besides those converts to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints who left for Utah in the 1850’s, other groups emigrated to South America–Uruguay and Argentina. Some emigrants went to South Africa. They also went to other areas of the United States. In the 1880’s and 90’s additional groups, who were not members of the Church, but related to member immigrants, came to Utah. Most of the time through the centuries, the Waldensians were extremely poor, partly because of spending all their efforts on their own security, but also because of heavy taxation. Often Catholics were exempt from taxation while they were forced to pay doubly. However, their hard work paid off in the fruit they obtained from their fertile soil. They grew vines for grapes, chestnuts, figs, olives and many other kinds of fruit. Silk production was a cottage industry. Higher up, the land was devoted to pasture, and there was an abundance of milk and wool. Enormous quantities of chestnuts were grown. They were dried and cleaned and the surplus sold or bartered for grain. They were an important source of food and could be made into biscuits. The following paragraphs are descriptions of the Waldensians taken from the writings of Marriner Cardon entitled “Children of the Valleys.” “There were two characteristics of their religious devotion that were frequently noted. The first was their knowledge of the scriptures. All classes studied the Bible, which from the 12th century onward they had in their popular tongue. Many, both men and women, could recite complete books of the Bible. Their pastors and missionaries often memorized — the New Testament.19 “Their second notable characteristic was the singing of biblical psalms. So common was it for the Waldensians to entertain themselves by singing psalms while working in the fields or about their homes that anyone found to be so engaged was presumed to be a Waldensian.” Two quotes from Catholic Inquisitors when writing against them, rather than condemning them, seem to be very complimentary: “‘The heretics may be known by their manners and by their language; for they are well ordered and modest in their manners; they avoid pride in their dress, the materials of which are neither expensive or mean…’ “‘They are such scrupulous observers of honor and chastity, that their neighbors, though of a contrary faith, entrusted to them their wives and daughters, to preserve them from the insolence of the soldiery. They are temperate in eating and drinking — they do not frequent taverns or dances. – They are on their guard against the indulgence of anger. They may be known also by their concise and modest discourse; they guard against indulgence in jesting, slander or profanity.’” From Reverend William S Gilly we learn the following: “– they form terrace upon terrace, in many places not exceeding ten feet in breadth and wall them up with huge piles of stone. Upon these terraces they sow their grain or plant vines. “— Picture this torn and rugged country, where neither carts nor beast of burden can penetrate and where the farmer is constrained to serve both as a cart and as a horse. I have seen slender women crushed under enormous weights during the summer months – picking up dirt at the foot of the mountain and carrying it on their back to the summit. In successive years the same soil, washed back down in the valley, is again carried up on backs a second, a third time, indefinitely.” “All the members of the family from eight years on had their part in the active life of the family, then almost entirely farming or pastoral. The heavy work was done by both men and women. Children looked after their younger brothers and sisters, herded livestock and helped with all the lighter work of farming and raising stock. —families ate meat only on special occasions. Baths were not frequent. — Births were attended often only by the grandmother of the baby. – One thing is astonishing, that [such] persons — should have so much moral cultivation. They can all read and write. They understand French, so far as is needful for the understanding of the Bible, and the singing of psalms.” — These observations give a few insights into the lives and homes of our ancestors.

APPENDIX C

Marie’s Dream

Marie Madeleine Cardon Guild [Charles] wrote an autobiography which describes much of the life of the Cardon family; it is priceless for our understanding of earlier events. We do not know if she began writing as some of the events happened or made notes of them. Possibly it was all written in her later life, but it was addressed to her children and edited in the year 1903, when she would have been 69 years old. [She was born 6 July 1834.] She was the sixth child of Philippe and Marthe Marie Tourn Cardon and the younger sister of Anne the subject of this brief biography. When Marie was six or seven years old in 1840 or 1841, she had a most remarkable dream which is often retold in family gatherings. In her dream she saw herself as a young woman. She was sitting on a small strip of grassy meadow near her home, watching over her father’s cows to keep them away from the vineyard. As she was reading, she looked up and saw three men approaching. She dropped her eyes being very much frightened. They told her not to be afraid, that they were teaching the gospel of Jesus Christ. They also said that her family would join his church and later emigrate to America. They gave her some small books and told her to study them. Quoting from her writing: “When I realized what had been said to me and what I had seen I became frightened. I took my clothes in my arms and ran downstairs to where my mother was preparing breakfast for our family and hired man. “As I came in she saw that I looked pale. She asked me if I was sick. I said ‘No.’ Just at that instant I was not able to talk. My mother told me to sit on a chair and she would soon see to me and learn what was wrong. Soon my father came in and my mother called his attention to me. She knew that if I was not sick that something had happened which caused me to look so strange. My father took me up, dressed me, and questioned me until I had told him all I had seen and heard.” As the years passed, Marie forgot her dream, but her father never did. Many years later her father Philippe also had a dream about21 missionaries coming. It reminded him of Marie’s dream. The very next day, when he was working at his stone masonry, one of his hired men told him he had heard of some missionaries teaching in another town. He went home mid-morning. His wife was very surprised and asked, “Why are you home at this hour?” and he replied, “I can see two strangers coming up the mountains bringing us a message concerning the gospel. I must dress in my best clothes and go down to welcome them.” He quickly changed into his Sunday clothes and began the long walk to find the missionaries. He walked that afternoon and all night and the next morning arrived in time to hear Elder Lorenzo Snow preach. He invited them to his home and to make it their headquarters. They went with him to the mountains. They asked about Marie, and the promise of Marie’s dream was fulfilled when they stood before her as she was seated in a meadow. Upon seeing them she remembered her dream and recognized them. They handed her a book and told her they were teaching of Jesus Christ. They held Sunday meetings at the Cardon home–sometimes forty or fifty or more were present. These were mountaineers who had arisen at two or three in the morning and walked for hours to hear the Elders teach. They baked bread in their big oven and cooked meat for many so that none would go away hungry before their long walk home. After doing what they could as a family to convert some of their friends and neighbors, they were told in a directive from the Church issued in 1853 to “come to Zion.” Their journey, beginning on February 8, 1854, has often been described, and it was a rigorous one. They traveled by carriage, railway, regular coach and a coach placed on sleds, drawn by sixteen mules up the steep mountain through ice and snow. Continuing by rail and steamer they finally reached Liverpool where they waited for their ship, the John M. Wood, to be completed. Their journey across the Atlantic took almost two months. Arriving in New Orleans May 2, 1854, they had to travel both the Mississippi and Missouri rivers by steamer. At Westport, now a part of Kansas City, Missouri, they prepared and began their pioneer travel overland with ox teams. Leaving in early May, as part of the Robert L. Campbell company, it took almost six months to reach Salt Lake City on October 28, 1854. They had walked for more than 130022 Much of the information in this appendix comes from the Autobiography of Marie Madeleine Cardon Guild, copied by DJS, April 8, 1909 by order of Mrs. Charles Guild, obtained via Edna Cardon Taylor. miles in the final phase of their nine month journey.